|

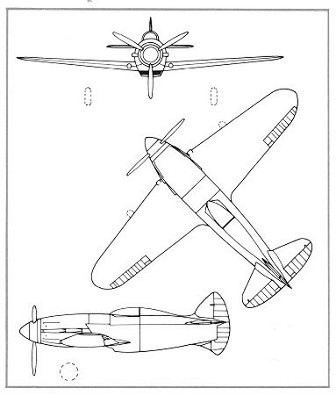

Napier-Heston Racer

Constructed exclusively for an attempt at setting the World’s

Landplane and Absolute Speed Record, the Nuffield-Napier-Heston J5 was

originally conceived by A.E. Hagg of D Napier and Son in 1936. Financial

arrangements for the patriotic venture were offered and provided for by

Lord Nuffield (the industrialist, Robert Morris, of MG fame). The order

for its general-arrangement and preliminary design work was begun in the

spring of 1938 by the Heston Aircraft CO, LTD, Middlesex.

The Heston project design department, headed by Chief designer George

Cornwall, was asked to design a super-fast aircraft intended to

recapture the world’s air speed record, then held by the Germans. The

racer’s design parameters were to be purposely designed around and

powered by a top secret, specially built, blown version of a

24-cylinder, 2,450 HP liquid cooled Napier Sabre

engine.

Napier Sabre engine

Napier Sabre engine

To ensure rapid construction and achieve a superfine finish, the

Napier-Heston Racer was built almost entirely of wood, which in part was

attributable to its beautiful lines. The racers weighed in at 7,200 lbs,

of which approximately 40% was the dry weight of the specially prepared

2,450 HP Napier Sabre engine. The racer’s potential top speed had been

reasonably placed at close to 500 mph If it had not been for the advent

of World War II, the Napier Heston racer may have proven itself the

fastest piston-powered aircraft of all time.

A rarebird indeed... regarded by many as the most beautiful design

achievement in the history of piston-powered flight. Special attention

was given by the designers to address the reduction of skin friction,

cooling drag and the elimination of parasitic drag caused by a “leaky”

engine cowling. The cockpit area was also given attention, besides

having a low-pressure outside airflow system and being sealed, a one

piece low profile persplex canopy was utilized for its aerodynamic

qualities. Within the remarkable high-gloss finish of the aircraft,

nearly 20 coats of hand-rubbed Titanine lacquer, could be found many

ingenious aerodynamic features that bear mentioning. From the absorption

of turbulent air at the mouth of the cooling duct, to the overall finish

achieved to reduce parasitic drag through skin friction and other

important airflow entries, especially the leading edge of the wings, no

scratches more than “half a thousand of an inch” deep were allowed.

One of the innovative aerodynamic design features incorporated by

Heston’s design group was the use of a multi-ducted belly scoop. For the

first time in the design of aircraft, an attempt was made to control and

clear turbulence from beneath the fuselage. The ducted scoop bled off

coolant air and yet provided a separate uninterrupted path for boundary

layer air to efflux on either side of the rudder, at the rudder post.

This new design preceded a similarly designed type belly scoop used on

the P-51 Mustangs for many years.

The wing of approximately straight taper form, had airfoil sections

of the bi-convex type, symmetrical throughout the greater part of the

span, with the maximum ordinate located unusually far back at 40% of the

wing chord to delay the onset of shock-stall which was expected at

higher speeds. A slight camber was given the tips to avoid tip stall

characteristics. The thickness-chord ratio was 16.2% at the fuselage,

12.8% at the landing gear fulcrum, and 9% at the tips. The wing as a

whole was aerodynamically “untwisted” and had a span of 32.04 feet, an

area of 167.6 sq. ft., with a wing loading of 43.5 lbs. per sq. ft.

High, but not considered bad for this type of aircraft. All control

surfaces were mass-balanced and provided with mass-balanced trim tabs,

the ailerons were of Frise type, none of the control levers or mass

balances projected in the slipstream. As was mentioned before, all

critical points, such as the leading edge of the wing, were polished

until no surface scratches more than a depth of 0.0005 in. remained.

In December 1938, construction work commenced on two Napier-Heston

prototype airframes side by side, in case there were problems with one

or the other. The design followed the Air Registration Board’s formula

for civil aircraft and were allotted the registration numbers, G-AFOK

and G-AFOL respectfully, work progressed on each very rapidly. By the

time war broke out on September 3, 1939, one aircraft, G-AFOK, was

nearing completion while the second airframe, G-AFOL, was approximately

60% completed. The start of war effectively put an end to work on the

second airframe, G-AFOL. However, work on G-AFOK was ordered to be

completed and the engine was run-up, the first for a Napier Sabre engine

in an aircraft, on December 6th, 1939 approximately one year after

construction began.

Ground engine testing of the “Racer” prototype began on the 9th of

February 1940, with Heston’s chief test pilot, Squadron Leader G.L.G.

Richmond beginning successful vibration and taxiing tests on the 12 of

March, 1940 and continuing them for several months. The “Racer” passed

all phases of the ground taxiing tests and prolonged engine run-up, the

newly designed aircraft seemed to have no faults.

It was decided to wait for perfect weather. Finally on June 12 1940,

Richmond decided to test fly the Heston racer. He taxied out without the

canopy. As the aircraft raced across Heston’s grass strip at full power,

control and response was more than adequate. Then the racer hit a bad

irregularity in the grassy surface very hard, causing the Heston to

rotate prematurely into a very nose-high attitude. Thirty seconds or so

after hitting the bump and full throttle and becoming airborne, the

engine coolant temps went critical. Richmond found himself in an

unfamiliar flight attitude in a new aircraft that employed a uniquely

designed and sensitive flight control system, the landing gear down and

no canopy. His first landing in the Heston was going to be hot.

Six minutes after opening the throttle, he had made a wide circuit at

about 20 mph, throttled back, and set up for the landing approach. The

ignition was not switched off and the DeHaviland-Hamilton constant-speed

prop was not feathered. Witnesses say that he leveled out at about 30

ft, stalled, and “banged it” on, quite possibly because he was being

scalded from below - there is speculation that an engine coolant pipe or

fitting had fractured during the hard bump incident at takeoff. Whether

the aircraft stalled or not, it arrived at the field at an excessive

rate of descent, hit the ground hard, drove the landing gear through the

wings, broke the tail, and ensued other major airframe damage before

coming to rest. The pilot was scalded but not badly hurt, the Heston was

a complete write-off.

The question since that

fateful day has been: Would the purposely built Napier-Heston Racer have

been capable of recapturing the world speed record? The racer never had

a chance to do so because of the circumstances that occurred. It’s

design is still regarded by many to have represented the pinnacle in

powered flight.

|