|

Amy

Johnson: Pioneer Airwoman

1903-1941

Amy

Johnson was born July 1, 1903, in Hull Yorkshire and lived there until

she went to Sheffield University in 1923 to read for a BA. After

graduating, she moved on to work as a secretary to a London solicitor

where she also became interested in flying. Amy began to learn to fly at

the London Aeroplane Club in the winter of 1928-29 and her hobby soon

became an all-consuming determination, not simply to make a career in

aviation, but to succeed in some project which would demonstrate to the

world that women could be as competent as men in a hitherto male

dominated field.

Her first important achievement,

after flying solo, was to qualify as the first British-trained woman

ground engineer. For awhile she was the only woman G.E. in the world.

Early in 1930, she chose her

objective: to fly solo to Australia and to beat Bert Hinkler's record of

16 days. At first, her efforts to raise financial support failed, but

eventually Lord Wakefield agreed his oil company should help. Amy's

father and Wakefield shared the 600 pound purchase price of a used DH

Gypsy Moth (G-AAAH) and it was named Jason after the family business

trademark.

Amy set off alone in a single engine

Gypsy Moth from Croydon on May 5, 1930, and landed in Darwin on May 24,

an epic flight of 11,000 miles. She was the first woman to fly alone to

Australia.

In July 1931, she set an England to

Japan record in a Puss Moth with Jack Humphreys. In July 1932, she set a

record from England to Capetown, solo, in a Puss Moth. In May, 1936, she

set a record from England to Cape town, solo, in a Percival Gull, a

flight to retrieve her 1932 record.

With her husband, Jim Mollison, she

also flew in a DH Dragon non-stop from Pendine Sands, South Wales, to the

United States in 1933. They also flew non-stop in record time to India in

1934 in a DH Comet in the England to Australia air race. The Mollisons

were divorced in 1938.

After her commercial flying ended

with the outbreak of World World II in 1939, Amy joined the Air

Transport Auxiliary, a pool of experienced pilots who were ineligible

for RAF service. Her flying duties consisted of ferrying aircraft from

factory airstrips to RAF bases.

It was on one of these routine

flights on January 5, 1941, that Amy crashed into the Thames estuary and

was drowned, a tragic and early end to the life of Britain's most famous

woman pilot.

Amy is remembered in many ways, one

of which is the British Women Pilot's Association award -- an annual Amy

Johnson Memorial Trust Scholarship to help outstanding women pilots

further their careers.

The World at Her

Feet: Amy Johnson Takes on Australia

Raul Colon

In 1930 the world took notice of a

different type of flyer. Amy Johnson was a newcomer to the world of long

distance flying, but in May of that year she took the aviation world by

surprise when she flew her single engine Gipsy Moth biplane, named

Jason; from London to Darwin. Although her nineteen days, eleven

countries journey did not break any aviation records, it represented a

breakthrough for women all around the globe. Many aviation enthusiasts

as well as much of the public in Europe and America were amazed at the

incredible feat accomplished by this unpretentious young woman from

Yorkshire, Great Britain. They were even more impressed at the fact that

before her ground breaking feat, Johnson had only eighty five hours of

actual flying experience!

Amy Johnson was born on July 1st, 1903,

months before the Wright Brothers introduced the world to aviation, in

Hull. Her father was a fisherman and raised young Amy to be a strong and

independent woman. Since her early teens, young Amy was keen to find her

place in the world, even if it meant entering into fields usually

associated with men. In the 1920s she attended Sheffield University for

a brief period before discovering that academic life was not suited for

her and her ambitions. After dropping collage, Johnson went on to work

with her father; from there she took a clerical position with an up and

coming advertising agency in downtown London.

Although those jobs offered her the ability

to pay the bills, Amy wanted more out of life. She wanted to live an

adventure, to live in the edge. She found that edge in flying.

She joined the prestigious London Aeroplane

Club in the summer of 1928 and quickly fell in love with aviation. As

she has done during all her life, Amy applied herself to this new task.

She earned her pilot’s license and a second one in ground engineering.

With those two licenses under her belt, Johnson went on to the aviation

community with a new sense of purpose, a new attitude. She was a shrewd

self promoter in a male-dominated environment. She tried to attract

patrons and donors in order to finance her dreams of making a difference

in the world. She always came up with interesting ideas on how to

promote her efforts.

Once she told a local newspaper reporter

that she was aiming to beak Bert Hinkler’s record of flying from England

to Australia. He did it in fifteen and half days during the spring of

1928.

Flying from the U.K. to Australia in those

early pioneers days must had offered any person one of the most

demanding challenges in human endeavour. The first to try were two

Australian lieutenants, Ray Parer and John McIntosh. After the Great War

ended, Parer and MaIntosh commenced preparations to fly to Australia

from their base in England. In 1920 they embarked on their challenge.

Utilizing a World War I vintage DH.9 biplane they began their trek.

Unfortunately for them, flying from the south of the U.K. to Darwin, was

a more demanding journey that the two young Australian lieutenants

hoped. Their DH.9 suffered numerous mechanical problems. It took them

forty days just to reach Cairo, Egypt. They crashed over Baghdad and had

the misfortune to spend six weeks in the jungle, before finally arriving

at Darwin with a damaged aircraft and a pint of fuel. During her

research into the planned trip, Johnson took more care in detail

planning than did the two Australians ten years before.

The first step for Amy was to secure the

necessary financial backing for the proposed enterprise. Financial

support was necessary for her endeavour to succeed. Her father offered a

credit line which enabled young Amy to quit her clerical job and to

purchase an aircraft. After securing her own plane, Johnson courted

prominent London personalities in an effort to gather the necessary

logistical backing needed for the planned adventure. One of those , Lord

Wakefield, the Castrol Oil Company magnate, played a key role in

securing fuel stores along the proposed flight path to the country down

under. The aircraft bought with her father's assistance was a de

Havilland DH.60G Gipsy Moth biplane. She named it Jason. Jason was a

small, single seat aircraft with an open cockpit design. Jason was

equipped with added fuel tanks for long distance flights. The DH.60G was

powered by a single, four cylinder, air-cooled engine capable of

generating 100hp. The engine gave the 60G a top cruising speed of only

eighty five miles per hours. But what the small aircraft lacked in

speed, it made it for in sturdiness and operational range. The most

important factor when operating over vast ocean distances. With the

necessary tools on hand, all that it was left for Johnson to do was to

actually attempt to fly to Australia, and fly she did.

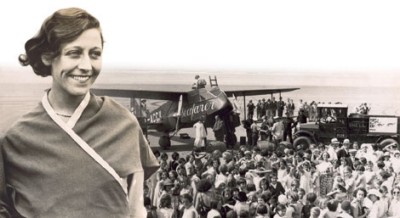

Amy Johnson took to the air for her

historic flight in the early hours of May 5th, 1930 A small crowd,

mainly family and friends, was gathered at the Croyden Airport to see

Amy off. The first phase of her trip called for crossing the English

Channel and then head up to the Asperne airport in Vienna, Austria. The

complete trip covered eight hundred miles, a distance she covered on the

very first day of her endeavour without any weather or mechanical

related problem. Next for Johnson, was the route from Vienna to

Istanbul, another eight hundred miles to cover. Again she covered the

distance without a problem, only fatigue bothered her. On May 7th, she

flew her 60G airplane over the rugged Taurus Mountains of Turkey, with

peaks as high as 12,000’. She aimed to land some five hundred and fifty

miles away, at the Aleppo airfield in Syria.

It was on this flight leg that Amy

encountered her first real test. While flying through turbulence at

8,000’, Johnson encountered dense cloud covered that forced her to fly

over a long stretch of mountainous terrain with minimal visibility. The

passes were difficult to manoeuvre in with unlimited visibility to begin

with, and now, without the assistance of a full spectrum of visibility,

Johnson was able to manage the narrow passages with pin point precision.

In some instances, her aircraft came within a few feet of hitting the

rocky edges of the mountains. After passing the mountains ranges,

Johnson elected to follow a railway line all the way into Aleppo. The

fourth day of flight brought massive storms along the Aleppo to

Baghdad route. This weather presented a problem for Amy. Up to this

point she was ahead of Hinkler’s record pace.

With an almost complete disregard for the

weather conditions, Amy took off from Aleppo in route to Baghdad, a four

hundred and thirty mile trek. During the first few hours of the flight,

Johnson did not encounter any major complications, weather or

mechanically related, but the trend did not last. Unexpectedly, a strong

wind gale forced her to dive relentlessly from her altitude of around

7,000’ to almost hitting the ground; it was at this point that she

decided to suspend the rest of the flight and land immediately in the

desert. There was nothing Johnson could do now but wait out the storm.

As suddenly as the storm front appear, it finished and Amy was able to

resume her flight within two hours after landing in the desert. Once in

the air, Amt promptly located the Tigris River and followed all the way

to Baghdad where she landed in a British-run airport on May 8th. The

following day, Johnson was airborne again, this time in route to Bander

Abbas, eight hundred and forty miles to the south-eastern part of the

Persian Gulf.

She covered the distance without a glitch.

May 10th saw her flying off to Karachi, seven hundred and thirty miles

way. When she landed at this British held city, she was received by the

residents as a folk hero. Her solo flight from London to Karachi in just

eight days was a record and most importantly for Amy, it put her two

full days ahead of Hinkler’s pace. Johnson did not have time to enjoy

the spoils of her success if she was to break the record. On May 11th

Amy took off her from Karachi to Allahabad, a city in British-controlled

India. In mid flight Amy discovered that the 60G’s fuel tanks were not

filled to capacity thus forcing her land nearly two hundred miles away

from her destination. While landing, her 60G suffered wing damages after

hitting a post. She quickly repaired the wing and after refuelling

her aircraft, thanks to a nearby local British garrison, she was once

again underway. After she reached Allahabad, she continued to the Dumdum

airfield in Calcutta, reaching it during the late evening hours of May

12th.

She was still on pace to break the record,

but now fatigue, not the weather on mechanical difficulties, started to

play a major role on her quest. Flying ten to twelve hours a day were

beginning to take their toll on the young woman from Hull. The next

phase of the journey called for a flight from Calcutta to Rangoon in

Burma, a journey of nearly six hundred and fifty miles. On May 13th she

departed Calcutta at 7:00 am; she encountered a weather front near the

Yomas range that forced her to deviate from the original flight plan.

She commenced tracking the Burmese coastline until she reached Rangoon.

Her target landing area was an abandoned race track, but due to the poor

visibility she landed on a soccer field. As was the case with her

emergency landing in the desert a few days ago, this forced landing

damaged her airplane’s wing structure and the engine propeller.

Fortunately, Johnson was a prepared woman and brought along with her a

new propeller.

The wing was repaired by friendly strangers

that appeared a few minutes after she landed. But the necessary repairs

took three precious days. She needed to get in the air quickly and in

the early morning hours of May 17th she took off from Rangoon in route

to Bangkok, three hundred and forty miles away. The weather again played

a key role in Amy’s quest. Constant rain drops and poor visibility posed

a major problem for Johnson, but she decided to press on to Bangkok,

again as it was the case a few days before, Amy found a railroad line

and followed it all the way to her destination. The days of May 17th and

18th saw Amy and her aircraft cruising over the Malaya Peninsula to

Singapore. This flight was uneventful and Johnson landed safely on

Singapore. The next phase of the journey called for a one thousand mile

trek covering the majority of the Dutch East Indies (present day

Indonesia). The original plan called for a trip to Surabaya in the

island of Java, but mechanical problems altered that path and Amy was

forced to land at Tjomal in the central section of Java.

After servicing her aircraft, Amy took off

from Surabaya on the morning of May 22nd with the aim of reaching

Atambua, nine hundred miles away. The flight was without weather or

mechanical problems, but poor navigation by the young Amy deviated her

from her original landing site. She landed at Haliluk, a remote tropical

area, twelfth miles away. By the afternoon of the 23rd, Amy finally

reached Atambua, the launching point for the final phase of her amazing

quest, Port Darwin, Australia. The last leg of the trip was probably the

most danger one. The journey called for Johnson to fly her DH60 airplane

over the Sea of Timor enroute to Darwin, a distance of five hundred

miles. The difficult part of the trip was that if any major situation

arise and Amy needed to crash land, the most likely place she would be

able to do it was the vast and isolated open waters of the Sea of Timor,

the ditching would probably have meant death since the area was seldom

used by commercial or military vessels at the time.

Amy Johnson departed on May 24th, Empire Day, almost three weeks since

the day she took off from Croyden Airport. The near eleven thousand mile

journey, that saw her pass over the deserts of the Middle East, the

jungles of the Indian subcontinent and the tropical islands of the Dutch

East Indies; was almost over. Since her departure from Atumbua the

weather was kind to Amy, she was even spotted by a Shell Oil Company

tanker, the Phorus, during her crossing of the Great Barrier Reef. The

tanker radioed in the news of Miss Johnson’s aircraft approaching Darwin

prompting several pilots to take off and try to meet her at mid air.

A task they failed to achieve.

But Amy did arrive in Australia at 3:30 in

the afternoon. When she landed, the young woman from Hull received the

acclaim she so desperately craved for. The local and international press

hailed the young and remarkable, inexperienced flyer from England. The

Prime Minister of Britain, Ramsey MacDonald, prominent dignitaries, even

the King and Queen of England called on young Amy to congratulate her.

Amy Johnson was at the top of the world. Becoming the first woman to

attempt and complete such a dangerous journey propelled Johnson to

celebrity status. The next decade saw Amy establish two more world

records, flying from London to Cape Town, South Africa. When World War

II arrived, Johnson enlisted in the Air Transport Auxiliary service,

ferrying aircraft from British factories to Royal Air Force bases. On

one of those ferry mission in January 5th, 1941, she crashed into the

Thames estuary and drowned in somewhat mysterious circumstances ending

the life of one of the most important figures in aviation history.

|