Coleman was born on January 26,

1892, in Atlanta, Texas, to a large African American family

(although some histories incorrectly report 1893 or 1896).

She was one of 13 children. Her father was a Native American

and her mother an African American. Very early in her

childhood, Bessie and her family moved to Waxahachie, Texas,

where she grew up picking cotton and doing laundry for

customers with her mother.

The Coleman family, like most

African Americans who lived in the Deep South during the

early 20th century, faced many disadvantages and

difficulties. Bessie's family dealt with segregation,

disenfranchisement, and racial violence. Because of such

obstacles, Bessie's father decided to move the family to

"Indian Territory" in Oklahoma. He believed they could carve

out a much better living for themselves there. Bessie's

mother, however, did not want to live on an Indian

reservation and decided to remain in Waxahachie. Bessie, and

several of her sisters, also stayed in Texas.

Bessie was a highly motivated

individual. Despite working long hours, she still found time

to educate herself by borrowing books from a travelling

library. Although she could not attend school very often,

Bessie learned enough on her own to graduate from high

school. She then went on to study at the Colored

Agricultural and Normal University (now Langston University)

in Langston, Oklahoma. Nevertheless, because of limited

finances, Bessie only attended one semester of college.

By 1915, Bessie had grown tired

of the South and moved to Chicago. There, she began living

with two of her brothers. She attended beauty school and

then started working as a manicurist in a local barbershop.

Bessie first considered

becoming a pilot after reading about aviation and watching

newsreels about flight. But the real impetus behind her

decision to become an aviator was her brother John's

incessant teasing. John had served overseas during World War

I and returned home talking about, according to historian

Doris Rich, "the superiority of French women over those of

Chicago's South Side." He even told Bessie that French women

flew airplanes and declared that flying was something Bessie

would never be able to do. John's jostling was the final

push that Bessie needed to start pursuing her pilot's

license. She immediately began applying to flight schools

throughout the country, but because she was both female and

an African American, no U.S. flight school would take her.

Soon after being turned down by

American flight schools, Coleman met Robert Abbott,

publisher of the well-known African American newspaper, the

Chicago Defender. He recommended that Coleman save some

money and move to France, which he believed was the world's

most racially progressive nation, and obtain her pilot's

license there. Coleman quickly heeded Abbott's advice and

quit her job as a manicurist to begin work as the manager of

a chili parlour, a more lucrative position. She also started

learning French at night. In November 1920, Bessie took her

savings and sailed for France. She also received some

additional funds from Abbott and one of his friends.

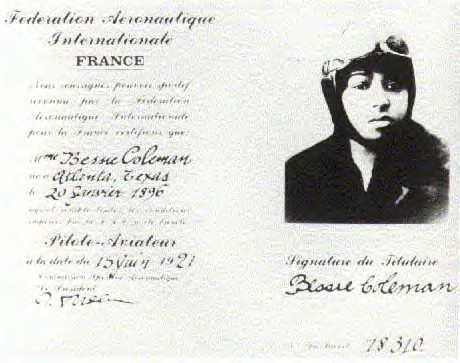

Coleman attended the well-known

Caudron Brothers' School of Aviation in Le Crotoy, France.

There she learned to fly using French Nieuport airplanes. On

June 15, 1921, Coleman obtained her pilot's license from

Federation Aeronautique Internationale after only seven

months. She was the first black woman in the world to earn

an aviator's license. After some additional training in

Paris, Coleman returned to the United States in September

1921.

Coleman's main goals when she

returned to America were to make a living flying and to

establish the first African American flight school. Because

of her color and gender, however, she was somewhat limited

in her first goal. Barnstorming seemed to be the only way

for her to make money, but to become an aerial daredevil,

Coleman needed more training. Once again, Bessie applied to

American flight schools, and once again they rejected her.

So in February 1922, she returned to Europe. After learning

most of the standard barnstorming tricks, Coleman returned

to the United States.

Bessie flew in her first air

show on September 3, 1922, at Glenn Curtiss Field in Garden

City, New York. The show, which was sponsored by the Chicago

Defender, was a promotional vehicle to spotlight Coleman.

Bessie became a celebrity, thanks to the help of her

benefactor Abbott. She subsequently began touring the

country giving exhibitions, flight lessons, and lectures.

During her travels, she strongly encouraged African

Americans and women to learn to fly.

In February 1923, Coleman

suffered her first major accident while preparing for an

exhibition in Los Angeles; her Jenny airplane's engine

unexpectedly stalled and she crashed. Knocked unconscious by

the accident, Coleman received a broken leg, some cracked

ribs, and multiple cuts on her face. Shaken badly by the

incident, it took her over a year to recover fully.

Coleman started performing

again full time in 1925. On June 19, she dazzled thousands

as she "barrel-rolled" and "looped-the-loop" over Houston's

Aerial Transport Field. It was her first exhibition in her

home state of Texas, and even local whites attended,

although they watched from separate segregated bleachers.

Even though Coleman realized

that she had to work within the general confines of southern

segregation, she did try to use her fame to challenge racial

barriers, if only a little. Soon after her Houston show,

Bessie returned to her old hometown of Waxahachie to give an

exhibition. As in Houston, both whites and African Americans

wanted to attend the event and plans called for segregated

facilities. Officials even wanted whites and African

Americans to enter the venue through separate "white" and

"Negro" admission gates, but Coleman refused to perform

under such conditions. She demanded only one admission gate.

After much negotiation, Coleman got her way and Texans of

both races entered the air field through the same gate, but

then separated into their designated sections once inside.

Coleman's aviation career ended

tragically in 1926. On April 30, she died while preparing

for a show in Jacksonville, Florida. Coleman was riding in

the passenger seat of her "Jenny" airplane while her

mechanic William Wills was piloting the aircraft. Bessie was

not wearing her seat belt at the time so that she could lean

over the edge of the cockpit and scout potential parachute

landing spots (she had recently added parachute-jumping to

her repertoire and was planning to perform the feat the next

day). But while Bessie was scouting from the back seat, the

plane suddenly dropped into a steep nosedive and then

flipped over and catapulted her to her death. Wills, who was

still strapped into his seat, struggled to regain control of

the aircraft, but died when he crashed in a nearby field.

After the accident, investigators discovered that Wills, who

was Coleman's mechanic, had lost control of the aircraft

because a loose wrench had jammed the plane's instruments.

Coleman's impact on aviation

history, and particularly African Americans, quickly became

apparent following her death. Bessie Coleman Aero Clubs

suddenly sprang up throughout the country. On Labour Day,

1931, these clubs sponsored the first all-African American

Air Show, which attracted approximately 15,000 spectators.

That same year, a group of African American pilots

established an annual flyover of Coleman's grave in Lincoln

Cemetery in Chicago. Coleman's name also began appearing on

buildings in Harlem.

Despite her relatively short

career, Bessie Coleman strongly challenged early 20th

century stereotypes about white supremacy and the

inabilities of women. By becoming the first licensed African

American female pilot, and performing throughout the

country, Coleman proved that people did not have to be

shackled by their gender or the colour of their skin to

succeed and realize their dreams.