|

Sir George Hubert Wilkins

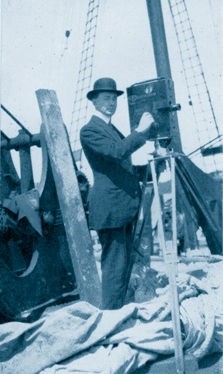

Wilkins as a young cinematographer. For 50 years

he would carry a movie camera on his adventures

George Hubert Wilkins

was born on 31 October 1888 at Mount Bryan, South Australia, 100 miles

north of Adelaide. He was the youngest of 13 children. His upbringing,

on the lonely farm at the edge of the Australian outback where he

witnessed devastating droughts, was a motivation for his life's work. In

1903 his parents moved to Adelaide and Wilkins enrolled in the

University but never completed his courses. He became interested in

cinematography and moved to Sydney where he worked in Australia's

pioneer film industry. He then left for England to work as a newsreel

cinematographer for Gaumont.

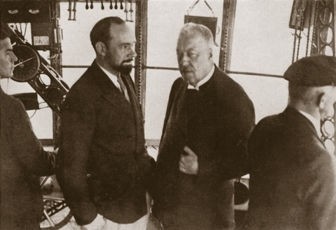

Wilkins with his camera aboard the expedition ship

Karluk. In the Arctic he developed his revolutionary ideas for polar

travel.

After moving to

London in 1909 Wilkins worked as a Gaumont cinematographer covering many

international events including the Balkans War in 1912. But he still

wanted to become a polar explorer. He was offered his first trip to the

Arctic as cinematographer with the Canadian Arctic Expedition of 1913

led by Vilhjamur Stefansson. He walked thousands of miles over

unexplored territory, learnt to live off the polar ice and developed his

revolutionary ideas for polar travel. In 1916 he returned to Point

Barrow, Alaska, to learn the world had been at war for two years.

Wilkins in World War One. Unarmed he led troops

into battle and became the only official Australian photographer in any

war to receive a combat decoration.

When he learnt about

the war, Wilkins went to France where he was appointed an official

photographer with the Australian War Records Office. From November 1917

until the end of the War Wilkins was responsible for Australia's

photographic record of fighting at the Western Front. He constantly

risked his life working forward of the front line and refused to carry

firearms. He became the only Australian official photographer, in any

war, to receive a combat decoration. He was awarded the Military Cross

twice. At the end of the war he travelled to Turkey to make a

photographic record of the battlefields of Gallipoli.

When he returned to England from Gallipoli,

Wilkins learnt that the Australian government had offered 10,000 pounds

for the first All-Australian crew to fly an aeroplane from England to

Australia. The Blackburn Aircraft Company, which had developed a long

range bomber during the war, had entered one of their planes. Wilkins

was appointed navigator

Wilkins replaced the Australian aviator Charles

Kingsford Smith in the England Australia

Air Race, but the Blackburn Kangaroo plane crashed with mechanical

problems in Crete.

With the other

members of the crew, the Blackburn Kangaroo left England on 21 November

1919. Problems were experienced with the engines and the plane was

forced down over France. Repairs were made and the flight continued, but

eventually, still with engine problems, the plane crashed landed in

Crete.

After the Air Race Wilkins returned to

England determined to continue polar exploration. He joined Dr John Cope

on the Imperial Antarctic Expedition. It was Wilkins first trip to the

Antarctic, but the expedition lacked funds and achieved little. Next

Wilkins was appointed Naturalist on what was to become Sir Ernest

Shackleton's last expedition to the Antarctic. This expedition left

London on the Quest, a ship that had been hastily prepared and

continually gave trouble. As it was being repaired in South America,

Wilkins went on ahead to South Georgia Island to photograph the flora

and fauna. When the Quest arrived six weeks later Wilkins learned that

Sir Ernest Shackleton had died on the voyage.

Wilkins work as

Naturalist on the Shackleton expedition so impressed the British Museum

of Natural History that they offered him an expedition of his own. The

Museum wanted to collect flora and fauna specimens from outback

Australia and the islands of Torres Strait. This became the Wilkins

Australia and Islands Expedition and for two years Wilkins travelled to

remote areas of Queensland, Northern Territory and the Torres Strait

filming, photographing and collecting specimens for the Museum. At the

end of the two years he wrote to the Museum saying he wanted to continue

his work in the polar regions.

Wilkins planned to fly over

the unexplored areas north of Alaska. He first purchased two Fokker

aircraft but found them too large for landing on ice. He sold one to

Charles Kingsford Smith who renamed it the Southern Cross and it became

the first plane to fly the Pacific Ocean. Wilkins bought a Lockheed

Vega. With pilot Carl Ben Eielson he flew across the Arctic Sea, from

Barrow in Alaska to Spitsbergen, Norway. It was the first time such a

plane flight had been made and the two men became international

celebrities. Wilkins was knighted and chose to be known as Sir Hubert,

rather than Sir George.

Wilkins was the first person to fly a plane in Antarctica. Unable to

find runways long enough he was beaten in the race to be the first to

fly to the South Pole.

With the same Vega

they had flown over the top of the world Wilkins and Eielson now

travelled south to explore Antarctica. They arrived at Deception Island

on the Graham Land Peninsula in November 1928. Their flights exploring

the Graham Land Peninsula were the first time anyone had flown a plane

in Antarctica. Wilkins had planned, if possible, to fly to the South

Pole, but on Deception Island he was unable to find a runway long enough

to get the Vega into the air with sufficient fuel to complete the

distance. Nevertheless it was the first time in history undiscovered

land was mapped from a plane.

Wilkins (left) aboard the Graf Zeppelin when it made the first round the

world flight in 1929.

Returning to America after his pioneering

flight in Antarctica, Wilkins was invited to be aboard the largest

airship of the period, the Graf Zeppelin, as it attempted the first

around the world flight. Wilkins agreed and joined the flight to make a

film record. The Graf Zeppelin flew from Lakehurst, New York, across the

Atlantic to Germany. From Germany it made the longest non-stop flight up

until that time - from Germany, across Russia to Japan. From Japan it

crossed the Pacific and America to return to New York. Six years later

Wilkins would be aboard the airship Hindenburg as it made its maiden

voyage from Germany to America.

Wilkins' Nautilus submarine in the Arctic in 1931. His pioneering

submarine expedition under the Arctic ice was 25 years ahead of its

time.

After a second season

flying his Lockheed Vega in Antarctica Wilkins planned his most

ambitious expedition. To take a submarine under the Arctic ice to the

North Pole. Constant delays prevented the submarine getting away on time

to reach the polar ice cap before winter and the submarine constantly

broke down. Still determined to prove that submarine travel under the

ice was possible, Wilkins continued north to the edge of the ice pack to

discover his submarine had malfunctioned again. Nevertheless, with his

partly disabled submarine he was still able to sail under the ice to

prove it could be achieved.

After his Arctic submarine expedition,

which many people considered a failure because he did not reach the

North Pole, Wilkins organised three expeditions to the Antarctic to

assist American millionaire explorer, Lincoln Ellsworth become the first

person to fly across the Antarctic continent. When Russian aviators went

missing while flying from Russia to America via the North Pole, Wilkins

was called in to head the search.

Wilkins Catalina Flying Boat during his search for missing Russian

aviators in 1937

In 1938 he returned

to Antarctic with Lincoln Ellsworth, again assisting in the discovery of

new land. At the outbreak of World War Two Wilkins immediately offered

his services to the Australian Government, but it had no need for a

polar explorer, now aged over 50.

Wilkins next offered

his service to the U.S. Army which retained him to teach Arctic survival

skill to U.S. soldiers. After the war he remained as a consultant to the

U.S. Army. The United States Navy were developing nuclear submarines for

sub ice travel in the Arctic and consulted Wilkins on his pioneering

1931 expedition. Wilkins died on 30 November 1958 in a hotel room in

Massachusetts. As a mark of respect the U.S. Navy took his ashes to the

North Pole in the nuclear submarine Skate. On 17 March 1959 the Skate

became the first submarine to surface at the Pole, where it held a

memorial service and scattered the ashes of Sir Hubert Wilkins.

|