Seven .

. . six . . . five . . . four . . . the numbers sound like a

doomsday atomic countdown. Suddenly, the pilot brings the

big aircraft up into a climb and over on its back. Then down

again, into a graceful loop that ends 15 feet over the

runway with the spectators about to panic from their seats.

Now the

crowd is nearly out of its mind. Tex Rankin, one of the

greatest stunt pilots of all time, turns to the man next to

him and shakes his head in disbelief. "You'd never catch me

doing that with that much airplane." Then he turns back,

eyes glued on the Ford Tri-Motor as Harold Johnson flying

solo, climbs for altitude to perform his most impossible

manoeuvre of the show. All that has gone before, has been

merely to whet the appetite and provide a few candidates for

coronaries.

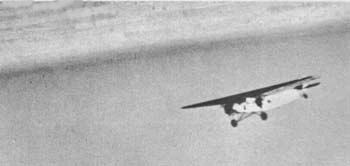

Typical wing-skidding landing during practice session at

Daytona Beach, Florida

At 400 feet,

Captain Johnson levels off then pulls the nose up sharply,

until the big tri-motor shudders into a hammerhead stall.

Over the top she goes and into a giant, arching spin toward

oblivion, her engines popping softly, the wind screaming

along her corrugated surfaces. At 400 feet there is only

room enough for a little over one turn. The Ford rolls out

at a very steep angle, and as Johnson seemingly recovers

from the spin and dives out of sight behind the bordering

trees, the people are frantic. They are certain that he has

crashed . . . but where is the explosion?

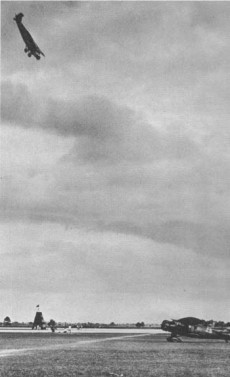

Famous for his low altitude pull-outs, Johnson eases the big

bird out of a loop at a delicate altitude while a Waco waits

to see what comes of it.

Safe on the

ground, Harold Johnson smiled. Always a showman, pleasing

the crowd was his foremost concern. If in the process, he

also petrified them, it was a minor by-product.

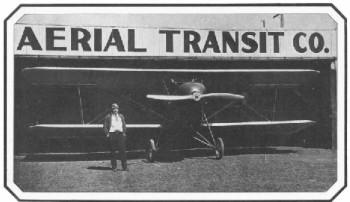

Captain Johnson's first aircraft, a WACO, in front of his

dealership hanger in 1930

After

pulling up from behind the trees still out of sight he had

wheeled the great silver ship around for a smooth one-wheel

landing, touching the tip of the wing on the dirt strip and

raising clouds of dust. So went Harold S. Johnson's life for

ten years - from 1932 to 1942. During that time, he became

known to millions as the "King of the Fords", and no crown

was ever worn more deservedly.

Today,

Harold Johnson recalls every detail of those fantastic

flying years as if they had happened last week. Born in

Chicago, Illinois in 1910, his first solo flight was made in

1929. The ship was a Waco and not long after soloing, Harold

formed the Aerial Transit Company and became a dealer for

the Waco Airplane Co. Still, he wanted to travel and decided

that a dealership was just too pedestrian for him. As a

result, he launched himself into the barnstorming business,

but with one important reservation. He knew that if he went

into an already overcrowded occupation, he had better come

up with something different . . . enter the Ford Tri-motor.

This was a

real first. It had never been done, much less attempted.

Stunting the big bird for air shows would really knock their

eyes out. So in 1932, Harold purchased a 4-AT Ford and set

about learning how to wring it out. Rolling a six ton,

multi-engine airplane was a job that required more than

guts, which Johnson had plenty of. It also demanded new

skills, new insights and new muscle coordination, as well as

brawn.

Harold

formed National Air Shows and with the Ford and other birds,

started zooming and looping over the towns and cities of the

East and Middle West. He soon discovered that wingtip

scraping cost him a new tip every six months, and other

maintenance problems so plagued the fledgling company that

Johnson was forced to establish a certified CAA repair

station on a Ford truckbed that followed the show.

Rare photograph shows Johnson being congratulated by Henry

Ford after putting on his typically daredevil demonstration

at the Ford plant in Dearborn, Michigan, during the early

thirties

Agility of the venerable Ford is demonstrated by inverted

flight

For the next

seven years Johnson, sponsored by SOHIO Oil, starred at the

National Air Races, stunting his Ford before thousands. And

in 1931, he placed 2nd in the Bendix Cross Country, flying a

Lockheed Orion. However, since he wanted a swift,

manoeuvrable biplane to work in the shows and no factory

built craft suited his fancy, he built his own.

Looping takeoff by Johnson in his Continental Special, then

in modified version. Johnson built this NR 10537, in

original version

In 1937, he

rolled out his Continental Special NR-10537. In this nimble,

Continental powered biplane, he would aileron roll straight

for the ground, fly upside down and generally warm up the

crowd for the main event. Then he would land, taxi up to the

Ford, hop out of one plane and continue the show in the

other. He never let the people relax. His usual procedure

would be a loop on take off, just to get everyone's

attention and, at times, Johnson would shut off one engine

and do his routine on two mills only.

Johnson

liked the Ford and the Ford liked Harold. Once, when he came

through Dearborn, Michigan, old Henry himself came out to

see him perform and went away amazed at his skill. The

crusty old gentlemen considered Harold "a most talented and

daring young man."

Looping the

Ford was Johnson's favourite manoeuvre and on one sortie

before a crowd of 15,000, he made 17 graceful loops,

breaking his own world record of 16. One of the more

interesting brain-storms Harold devised, was to mount the

Continental Special atop the Ford, so that both aircraft

could be flown to various air shows by one pilot. Somehow,

this project was put aside and never reached completion,

although the feat was accomplished later both by Great

Britain and Germany.

Pearl

Harbour brought the National Air Races to an end. Harold

sold the Ford and started ferrying Hudsons across the stormy

Atlantic to England The loss rate on those wartime delivery

routes was nearly 50 percent then, and the missions were

hairy, most of them bedeviled by malfunctions of major

proportions. After a year of this incredible type flying,

Johnson took on the less hazardous job of testing B-24's for

Ford's Willow Run plant. These fat birds were a far cry from

the kind of ship he liked to fly and he soon transferred to

sunny California and Lockheed.

In 1944, he

checked out in P-38s and began testing planes for delivery

to the combat zones. It was interesting and demanding work,

with his day filled by 7 plus G pullouts. Johnson also

tested the 1049 Constellation and found, to his delight,

that the rate of roll was better than the P-38's . . . but

there were more surprises in store.

At the close

of hostilities, the P2V was a brand new idea at Lockheed and

there was a rush on to complete tests to prove to the Navy

that the P2V was the bird they wanted for anti-submarine

patrolling. On a great flying day over Burbank, Johnson was

letting down the X model prototype, when the bomb door came

loose, wrapped itself around the tail, smashed the rudder

and ripped three fourths of the vertical fin off the

aircraft. Johnson fought for control of the big ship, and

heading out over the desert, saved the plane and the P2V

program by landing the aircraft at Edwards AFB. Thanks in

part to Harold Johnson's superb skill and piloting ability,

the P2V is now the standard anti-submarine patrol bomber for

the free world.

During the war, Johnson was test pilot on B-24's at Ford's

Willow Run plant, flew P-38's for Lockheed and ferried

Hudsons to England.

The hectic

years were now coming to a close. With hostilities over in

the Pacific and military planes no longer being built in

quantity, test pilots went looking for other areas in which

to apply their specialized talents. The King of the Ford

became a Beechcraft distributor in the east, but he had

found a home in California and was back a few years later to

open a shop at Van Nuys Airport. Nevertheless, neither he

nor the tin goose could stay separated for long. There was

another Ford in his future . . . G.E. Moxon's Ford 5-AT at

Santa Monica Airport . . . where Johnson now works daily to

restore it. And who knows, maybe a new generation of

aviation buffs will see Captain Harold Johnson fly the six

ton airliner through a loop or roll? At any rate, a Classic

Airman and a Classic Airplane are back together again.