|

Jimmie and Walter Wedell

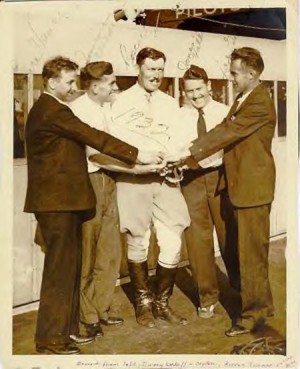

Trophy presentation to James Wedell and Mary Haizlip in New

Orleans. L to R: James Doolittle, Mary Haizlip, James Wedell

Jimmie and Walter Wedell

Jimmie Wedell was

born in Texas City, Texas, in 1900. His mother died when he

was only an infant, and he was raised by his father, who

tried to make ends meet as a bartender. This often left

Jimmie in charge of both the home and his younger brother,

Walter. A resourceful young man, Jimmie demonstrated his

mechanical aptitude at an early age. He quit school after

the ninth grade and soon transformed four bicycle wheels, a

one-cylinder Yale motorcycle engine, and various parts into

an automobile. This hobby turned into a means for Jimmie to

pursue his greater passion, aviation.

A motorcycle

accident that blinded his right eye barely slowed him down.

Prior to World War I, he rebuilt two crashed airplanes, an

OX Standard and a Thomas Morse Scout, into one flyable

craft, although he had never flown in one. Soon thereafter

he met a barnstormer who gave him a one-hour lesson. The

rest, including how to take off and land, he learned by

trial and error. He then engaged in barnstorming for his

livelihood.

With this

self-taught knowledge of flight, Wedell tried to join the

army as an aviator during World War I. Much to his

disappointment, he was rejected because of his eye. While

Walter began a four-year hitch in the navy, Jimmie, with his

Colt .44 for protection, headed for the Texas-Mexico border

where he ran guns and transported rumrunners. After the war,

Walter joined Jimmie in this endeavour. As time passed and

technology improved, the Wedell brothers’ planes proved no

match against the newer United States government planes now

patrolling the border. Jimmie managed to circumvent this

situation temporarily by flying exclusively at night.

Eventually, however, the idea to build his own, faster plane

dawned on him.

Wedell-Williams

Air Service

In 1929,

Jimmie Wedell and Harry Williams formed the Wedell-Williams

Air Service. A landing field was cleared on Calumet

Plantation, land that had been part of the Williams sugar

fields near Patterson. Eventually, the air service expanded

until Patterson was home base for a flight school, aerial

photography, amphibian service, and aerial transportation.

Harry Williams continued to develop the airport through the

1930s, constructing an additional hangar, improving the

field’s drainage, and installing lights for night

operations. At one point, Williams was the owner of the

largest privately owned fleet of aircraft in the world, with

forty-two planes.

Although

remembered as shy and reserved, Jimmie had the flair of a

showman. As an early company publicity stunt, he convinced

Walter and his fiancée Henrietta to marry in the air in one

of their Ryan cabin planes. Flower girls draped the plane

with flowers before it left, and a New Orleans radio station

broadcast the vows. Jimmie flew the plane and served as the

best man.

Walter Wedell with Menefee Airways Plane

Wedell-Williams

Air Service began with two routes originating in New

Orleans: a weekly flight to St. Louis with stops in Jackson,

Mississippi, and Memphis, as well as a daily run from Baton

Rouge to Alexandria to Shreveport, and later, to Dallas–Fort

Worth. The company also established an aviation school at

Menefee Airport in Chalmette, with branches in Alexandria,

Baton Rouge, Patterson, and Gulfport, Mississippi. Wedell-Williams

was awarded a government contract for airmail service

between New Orleans and Houston in 1934.

Wedell-Williams Staff with "44"

At the

Patterson facility, a team of engineers and mechanics began

to manufacture airplanes for both sport racing and mail use.

In later years, Wedell-Williams would be remembered almost

exclusively for its racing exploits. In reality, the service

also owned many other types of aircraft, including a Ryan

monoplane, Lincoln Page, Travel Air, Ryan B-7, Lockheed

Sirius, and several Lockheed Vegas.

The

First Wedell-Williams Racers

In late

1929 Wedell-Williams began construction on its initial

racing design. The first plane was a racer named the

We-Will, derived from the first parts of the pair's last

names. Completed in early 1930, the We-Will was powered by a

Hisso engine left over from Jimmie’s barnstorming days. The

second model was basically built to meet mail plane

specifications, since Harry Williams planned on bidding on

the mail route service from New Orleans to Shreveport and

Dallas.

Jimmie

Wedell became famous for radically new designs that set

speed records time and again. Among the first constructed at

the Patterson plant was the We Will Jr., which Jimmie flew

in the 1930 American Flying Derby as No. 17. The

All-American Derby, a cross-country race featuring eighteen

planes, left Detroit, Michigan, on July 21, 1930. From

Detroit, the racers traveled a path to Buffalo; Cincinnati;

Little Rock, Arkansas; Houston; San Angelo, Texas; Douglas,

Arizona; Los Angeles; Ogden, Utah; Lincoln, Nebraska; and

finally back to Detroit. The 5,541-mile trek lasted eleven

days. After staying in contention for most of the race,

Jimmie experienced engine trouble leaving Los Angeles and

finished eighth, collecting $1,600 in prize money.

A fierce

competitor, Jimmie was bitterly disappointed by this finish.

He returned to Patterson to prepare the racers for the

Chicago National Air Races, August 23 to September 1, 1930.

He brought three planes from Patterson to Chicago. The first

was the We-Will Jr., piloted by Wedell. He managed no better

than third in the 350-cubic-inch free-for-all. The second, a

We-Will, had engine problems and never competed. The third

plane was the We-Winc, piloted by Everett Williams (no

relation to Harry), who finished second in the

800-cubic-inch free-for-all and in the 1000-cubic-inch

free-for-all. All in all, 1930 was not a promising start for

Wedell-Williams racing planes.

We-Will (sideview) at the New Orleans airstrip just outside

of one of the hangars. 1930

1931 Racing

The airframe

of the damaged We-Will was used as the starting point for a

new design, which Jimmie hoped would be capable of winning

the coveted Thompson Trophy. This was the first racer to

bear the famous number "44." At the 1931 National Air Races,

few people outside those pilots who had flown with him had

heard of Jimmie Wedell. After his arrival in the "44,"

called the mystery ship of 1931, there was no doubt that

Jimmie Wedell was a powerful force. So great was his debut

that Roscoe Turner immediately ordered a Wedell-Williams

plane. The "44" was designed as a pylon racer and was not

yet tested for endurance flying, so Jimmie kept it out of

the Bendix. Wedell finished second in the prestigious

Thompson Trophy Race, claiming a $5,850 prize.

Featuring

eight to ten planes on the starting line, the Thompson

Trophy Race was the grand finale of each year’s National Air

Races. Its purpose was to honor the fastest airplane that

could be built. There were no restrictions. Any power of

engine could be used, any number of engines, any number of

pilots, and any weight.

Wedell-Williams "44"

Nearly one

hundred planes took part in the celebration of the opening

of the new $200,000 Baton Rouge airport in June 1931. The

newly outfitted We-Winc was the winner of the open

free-for-all race for engines under 800 cubic inches, by an

unheard-of margin of two miles. Jimmie won the event’s main

prize, the Alvin Callender Trophy, for his performance.

In November

1931, Jimmie prepared to leave Los Angeles in an attempt to

smash James Doolittle's transcontinental speed record. While

waiting for bad weather to clear, Wedell heard of Captain

Frank Hawks's pending attempt to break the Three Flags (Agua

Caliente, Mexico, to Vancouver, Canada) record. Jimmie

decided on an informal race with Hawks, just to "kill time."

With this spontaneous trip, Jimmie set a new record of six

hours, forty minutes, breaking the old one by one hour and

eight minutes. The two men flew the same course, with Wedell

starting in Mexico and Hawks in Canada. An over flight of

Vancouver cost him fifty-five minutes, but Jimmie had not

thought it was possible to arrive in less than six hours, so

he kept on flying. Only the previous summer, Roscoe Turner

had held this same record with a much slower time of nine

hours and fourteen minutes. Hawks was overcome in his

cockpit by carbon monoxide and unable to complete the trip.

The

following week, convinced that he could make the

transcontinental trip in less than ten hours and armed with

messages of encouragement from such notables as Louisiana

Governor Huey P. Long and Orleans Levee Board Chairman Abe

Shushan, Jimmie left Los Angeles in an attempt to break

Doolittle’s record of eleven hours and sixteen minutes.

However, the flight was cut short after bad weather,

including high headwinds, which slowed the plane to as

little as ninety miles per hour, and snow over Colorado,

ruined his chance for the record.

1932 New Racers

1932 marked

the beginning of the era of Wedell-Williams air-racing

dominance. First up was the Three Capitals record, a flight

from Ottawa to Mexico City through Washington, D.C. Jimmie

left Ottawa on March 23, 1932, and landed in Mexico City

eleven hours and fifty-four minutes later, breaking James

Doolittle’s record by thirty minutes. Wedell claimed that

his time would have been considerably better if not for

strong headwinds.

Next was the

2,041-mile Bendix, which began the National Air Races and

followed a route from Los Angeles to Cleveland. Jimmie flew

the 1932 version of the "44," Miss Patterson. Jim Haizlip

was contracted to fly the "92," Miss New Orleans, as well as

another "44." Roscoe Turner flew his "44," known as the

Gilmore or by its race number, 121. On August 29, 1932, Jim

Haizlip won the Bendix with a time of eight hours and

nineteen minutes and continued to New York to break Jimmy

Doolittle's transcontinental record by fifty-seven minutes,

with a time of ten hours and nineteen minutes. After leading

for a large portion of the race, Jimmie Wedell came in

second and Roscoe Turner placed third, a 1-2-3 victory for

the Wedell-Williams Air Service. After the long flight, Jim

Haizlip remarked, "It’s nice to be with people again. It was

awful lonesome over the canyons."

Pilots gathered before the start of the 1932 Bendix Race.

Second from left, Jimmie Wedell; centre, Roscoe Turner.

Test flights

on the newly improved "44" took place during the weeks

leading up to the 1932 Thompson Trophy Race. The plane’s

original 300-horsepower engine was supercharged to produce

more than 525 horsepower. One test flight on the ninety-mile

flight from Patterson to New Orleans took only seventeen

minutes, an average of 324 miles per hour. All three Wedell-Williams

racers were also entered in the Thompson Trophy Race. Jimmy

Doolittle dominated, flying the Gee-Bee 7-11. He lapped the

entire field, except for Wedell. Jimmie took second, Roscoe

Turner third, and Jim Haizlip fourth, this time a 2-3-4

Wedell-Williams finish. This was the final air race for

Doolittle. After flying the dangerous and highly unstable

Gee-Bee, Doolittle decided that he was lucky to be alive and

put his racing days behind him.

Upon

returning to Patterson after their remarkable showing at the

1932 races, Jimmie Wedell and Jim Haizlip roared down Main

Street in Patterson, side by side, at 300 feet and 280 miles

per hour. Jimmie proceeded with the "44" to the first annual

New England Air Pageant, which dedicated the Rhode Island

State Airport. He easily won all three events that he

entered.

1933 World Speed

Record

Fresh

off his successes at the 1932 National Air Races, Jimmie

flew Miss Patterson to Florida for some additional

competition. After demolishing the other contestants in his

first two races, the "44" was ruled too powerful for further

races. So much did he enjoy the thrill of the chase that

Jimmie borrowed a Warner monocoupe from a friend and

proceeded to win three more races without Miss Patterson.

In 1933

Jimmie began testing a new design, the "45." Mechanical

difficulties forced him to leave the plane in Patterson for

the 1933 New York to Los Angeles National Air Races, so its

Pratt and Whitney Wasp 985 engine was mounted on the "44."

Jimmie finished second in the Bendix, beaten by Roscoe

Turner, who flew his Wedell-Williams with the more powerful

Hornet engine. Roscoe and Jimmie were the only two

contestants even to finish the race. The "92," flown by

famous racer Lee Gelbach, was forced down with mechanical

difficulties near Indianapolis. The Thompson Trophy Race

resulted in another 1-2-3 Wedell-Williams victory with

Roscoe again in first place. Roscoe was later disqualified

for cutting a pylon, and the 1933 Thompson Trophy was

awarded to Jimmie Wedell, with Lee Gelbach second in the

"92."

Jimmie Wedell standing in the cockpit of the "44" at the

Landspeed Race 1933. You can see the other planes lines up

down the field.

In addition

to the overall world speed record, he broke records flying

between New Orleans and several cities while transporting

Times-Picayune photographs of Tulane University football

games. After the Georgia game in 1931, Jimmie flew from

Atlanta to New Orleans in one hour and fifty-seven minutes.

After the Georgia Tech game in 1933 he flew through two

thunderstorms and still managed to return from Atlanta in 1

hour and 41 minutes, improving his own record. Showing a

more serious side, Wedell gained a reputation as a "mercy

flier" after he conducted several aerial searches for

persons lost in the swamps and on lakes. He made national

news when he flew through fog and heavy crosswinds to rush a

West Columbia, Texas, baby, Sue Trammel, to Baltimore’s

Johns Hopkins Hospital for a brain operation.

So

impressive and overwhelming was Wedell’s success to this

point, that other racers actually avoided races in which

they knew Jimmie would be flying. At the 1933 National Air

Pageant, a charity event held at Roosevelt Field in New

York, only one other flier even entered the measured course

speed trial event against Jimmie.

Death of Jimmie

Wedell

On June 24,

1934, aviation suffered a crushing blow when Jimmie Wedell

died in a plane crash. At the time of his death, Wedell was

recognized as the speed king of the world, aviation’s most

successful designer of racing planes, and the holder of more

records than any other flyer. Syndicated columnist Will

Rogers added, "Who knows but what aviation might not be

permanently set back 100 miles an hour through the loss of

this fellow, with the knowledge that was buried with him?"

History has incorrectly blamed the accident on a student

pilot, Frank Seeringer, of Mobile, Alabama, who supposedly

froze at the controls of the DeHavilland Gypsy Moth. It

appears that Jimmie was at the controls when the crash

occurred in Patterson, probably due to structural failure.

Jimmie was buried in West Columbia, Texas, following

services held in New Orleans.

Plane Crash of Jimmie Wedell

Plane Crash of Jimmie Wedell |