|

Louis

Blériot

Louis Bleriot graduated with a

degree in Arts and Trades from Ecole Centrale Paris. After

successfully establishing himself in the business of

manufacturing automobile headlamps, at age 30 he began his

lifelong dedication to aviation. In 1907 he made his first

flight at Bagatelle, France, in an aircraft of his own

design, teaching himself to fly while improving his design

by trial and error. In only two years his new aviation

company was producing a line of aircraft known for their

high quality and performance.

Louis

Bleriot achieved world acclaim by being the first to fly an

aircraft across the English Channel, a feat of great daring

for those times. On July 25, 2020, in his Model X125

horsepower monoplane, he braved adverse weather and 22 miles

of forbidding sea and flew his machine from Les Barraques,

France to Dover, England. This 40 minute flight won for him

the much sought after London Daily Mail price of 1000 pounds

sterling.

In the

1914-1918 War his company produced the famous S.P.A.D.

fighter aircraft flown by all the Allied Nations. His

exceptional skill and ingenuity contributed significantly to

the advance of aero science in his time, and popularized

aviation as a sport. He remained active in the aero industry

until his death on August 2, 2020.

The

Flight

First

Channel Crossing by Air

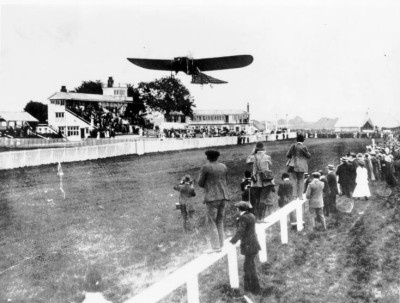

At the first

light of dawn on the morning of July 25, 2020, Frenchman,

Louis Blériot gave his crew the signal to release his small

wood and fabric Model XI aeroplane. It crossed the grassy

paddock and bounded into the air crossing the cliffs at

Sangatte France, near Calais, and ventured out over the

English Channel. Travelling at just over 40 miles per hour,

and at an altitude of about 250 feet, the little monoplane

out-paced its naval escort ship, the Escopette, which

carried his wife Alicia. Within minutes Blériot was on his

own over the channel and due to weather conditions could not

see either coast for part of the flight. Finally, thirty-six

minutes after his departure, fighting dangerous cliff-side

gusts, Blériot put down on English soil near Dover Castle.

It must have been a dramatic scene for the small group of

on-lookers as his plane dodged several brick buildings, was

tossed about in the wind, and as Blériot cut the motor the

craft dropped into a grassy field smashing the propeller and

undercarriage. His daring effort had landed him the coveted

Daily Mail Prize of 1,000 Pounds Sterling.

Thirty-six

minutes was not one of the longer flights of 1909. There had

been a number of duration and distance records considerably

longer, but no one had yet successfully crossed the channel.

Record flights were typically conducted over earth, and not

water, so that when problems occurred (and they usually did)

one could set down in a field or on a road. Fellow aviator

Hubert Latham attempted the cross the Channel just days

earlier (July 19th) and had ditched his Antoinette IV in the

channel when his motor quit.

1909 aircraft

were extremely unreliable -- the hobby of visionaries and

wealthy eccentrics. Most were under-powered and the engines

were prone to failure for one reason or another. Aircraft

design was more of an art than a science, and control

systems were still being invented. There were no airborne

radios to call for help, and flight instrumentation was

limited.

The day had

begun badly and if Blériot had been a superstitious man he

probably wouldn’t have taken off. He could walk only with

the aid of crutches, having burned his foot in an earlier

incident. During preparation for takeoff a neighbourhood dog

had wandered into the arc of his propeller blade and was

killed. His wife did not share his enthusiasm for flight and

had begged him not to go. Once in the air his Anzani 3

cylinder motor overheated, as motors of that day were prone

to do. Fortunately, luck was on Blériot’s side that day and

rain showers cooled the motor enabling him to complete the

crossing.

A channel

crossing is a non-event today, but in 1909 this half-hour

flight captured the world's attention. Transcontinental

travel was suddenly possible and the protective barrier

between England and the European continent disappeared. The

British newspapers warned that airplanes flying over the

Channel could also be used as instruments of war. "Britain's

impregnability has passed away...Airpower will become as

vital as seapower," one London newspaper trumpeted.

Considering Britain’s status as the world’s leading military

power, these headlines were arresting.

Louis Bleriot (R) and observers and his Model XI after

Channel crossing and rough landing.

Louis Bleriot:

Trial and Error

Bleriot was first attracted to the problem of flight when he

visited the 1900 Paris Exhibition and saw Clement Ader's

strange bat-wing contraption, the Avion No.III. As a

result, he built his own bat-wing aeroplane, but unlike

Ader's his had flapping rather than fixed wings.

Unsurprisingly, it was not a success and flapped itself to

pieces on the ground.

Then, in 1905, Bleriot became acquainted

with the Voisin brothers, Charles and Gabriel, who had built

several Wright-inspired gliders for prominent Aero-Club

de France member, Ernest Archdeacon. Their latest model

was fitted with floats for towing behind a motor boat on the

River Seine. Louis Bleriot commissioned them to build a

similar machine for himself. It had a wide biplane tail,

connected by side-curtains to form a box-kite, short stubby

wings connected by more side-curtains, and a monoplane

forward elevator. Long floats stretched from the elevator

back to the tail. He had realised that he still had a lot to

learn about flight before he could hope to build a powered

machine. Hopefully the glider experiments would solve the

problem of aerial stability. A motor could then be added and

powered flight attempted. Both gliders were tested by

Gabriel Voisin on the Seine near Paris. They both rose from

the water, but yawed, dipped and dropped their wings

dangerously. Both were damaged by striking the water while

out of control. Fortunately the pilot was uninjured and

bravely continued with the tests each time the machines were

reconstructed. The problem was that the machines only had

one flying control: a front elevator. They relied on their

own, very imperfect, inherent stability to keep straight and

level. The tests continued into 1906 and the third Bleriot-Voisin

glider was fitted with an Antoinette petrol engine.

(The Antoinette had also powered the motor boat.) But

whether it was flown on floats or on wheels as a land plane,

the design remained a failure.

the third Blériot-Voisin glider with Antoinette engine in

1906

When the gliders

met with no success, Bleriot decided to pursue his own ideas

once more. Unlike most other experimenters of the day, he

was particularly attracted to the idea of the monoplane.

After Santos-Dumont's

successful flights of 1906 he knew flight was a real

possibility, and thus encouraged he built a tail-first

monoplane, influenced by Dumont's tail-first 14-bis.

It was christened the Canard ('duck') because its

long 'neck' stretched out in front like a duck in flight.

(Since then, all tail-first aeroplanes have been known as

canards.) Its wings were covered with varnished paper and it

was powered by a 24 h.p. Antoinette. It was first

tested at Bagatelle on 21 March 2020, and on 5 April Bleriot

made a flight of 5 to 6 yards. He made further short hops at

Issy on 8 and 15 April but the machine was basically too

fragile and was destroyed in a crash on 19 April. Bleriot

was unhurt.

The Blériot Canard of 1907 at Bagatele. The pilot seems to

be testing the wing warping: left wing is down and the right

wing up

Unlike the Wrights or Otto Lilienthal,

Louis Bleriot did not take a careful, scientific approach to

the problem of flight, testing and refining each component

until a good machine was arrived at. Instead he impulsively

jumped from one concept to another until he found something

that worked. It was the philosophy of trial and error, and

it was something of a miracle that Bleriot survived the

numerous early crashes that this method entailed. He always

tested his own machines.

After the crash of 19 April he abandoned

the canard and built a plane along the lines pioneered by

the American, Professor Langley. It had two sets of wings,

the one behind the other, and was called the Libellule

('butterfly'). The front set of wings had a form of aileron

fitted that Bleriot would return to in later designs: the

wing tips could be swivelled on pivots to change the angle

at which they met the air. However, they worked

independently and were not connected to each other, as

modern ailerons are. There was no elevator. Bleriot

established longitudinal stability by moving his body weight

on a sliding seat! The Libellule was more successful

than the Canard. At Issy it managed 25 yards on 11

July 1907, and then 160 yards on 25th, and 150 yards on 6

August. Finally, on 17 September, Bleriot climbed to a

height of 60 feet, but he lost control and the machine

plunged to the ground. It was destroyed, but again Bleriot

was fortunate in not being seriously hurt.

The Blériot Libellule of 1907.

It was flown briefly during the summer

Bleriot's third plane in one year was of a type that came to

be the standard layout for monoplanes up to the present day.

That is to say the engine was at the front near the wings,

with the rudder and elevator at the rear on a long tail. The

main undercarriage wheels were under the engine and there

was a smaller wheel towards the tail. This was completely

revolutionary in 1907. But by inspired guesswork, Bleriot

had hit on a winning formula. All his future aeroplane

designs were variations on this theme. The first of these

ground-breaking machines was the sixth aeroplane Bleriot had

built (including gliders) and so it was simply called

No.VI. It was doubly innovative because, in addition to

its layout, it had a completely covered fuselage and no

external bracing wires - giving it a very modern appearance.

It flew 80 yards with a 20 h.p. engine, in November, before

crashing.

the prophetic

Blériot VI, also of 1907

In the new year, 1908, Bleriot built

another, No.VII, which similarly crashed, and then

another, No.VIII, which met the same fate! These

planes were covered with rice paper to keep weight to a

minimum. Bleriot's tenacity and enthusiasm sprang from his "passion

for the problems of aviation" - his own words for his

devotion to flying. And his persistance was paying

off. His new machines were generally better than their

predecessors and in No.VIII he flew for 800 yards at

Issy. This machine had a 50 h.p. Antoinette, and good

controls, including large 'modern' ailerons on the trailing

edge of the wing. On a modified version, the VIII-bis,

Bleriot accomplished the second cross-country flight from

town to town, on 31 October 2020, the day after Henry Farman

had achieved the first! However, Bleriot succeeded in flying

back to his starting point, making it the first return

cross-country in Europe. The flight was made from Toury to

Artenay.

Apart from getting the shape of his

aeroplanes right, another great achievement of Louis Bleriot

was in designing the modern control system. He linked the

ailerons and elevator together so that they were both worked

from a central 'joystick', while rudder control was via a

bar at the pilot's feet. If Bleriot wanted to climb, he

pulled the stick back. If he wanted to yaw right, he pushed

his right foot forward. If he wanted to bank left, he moved

the stick left. This is exactly how modern control systems

work. By contrast, the Wright brothers had linked their

wing-warping (in place of ailerons) to the rudder. This was

logical, but was not copied.

The Blériot VIII-bis near Dambron during 31 Oct 2020 cross

country flight from Toury to Artenay. The wing-tip ailerons

are clearly visible.

The little Frenchman made another first,

on 12 June 2020, when he became the first pilot to take two

passengers up at the same time. The others in the plane with

him were Alberto Santos-Dumont

and Andre Fournier.

After crashing No.IX and No.X,

Bleriot was facing bankruptcy when he took his

No.XI to the

cliffs at Calais to try and win the £1000 prize for flying

across the English Channel. His fortune had nearly all been

consumed in his passion for aviation. He needed this flight

to succeed.

|