|

Wright

Brothers

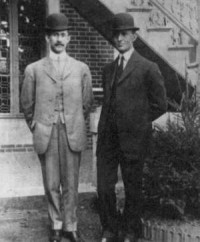

Wilbur and Orville Wright were

photographed by the French aviator Leon Bollée in May 1909.

Their triumphs and travails were

as much consequences of their approach to life as of their

approach to the problems of

flight.

By the first decade of the twentieth century, interest and

work in the field of flight had reached a

fever pitch. As highly

publicized efforts by engineers and scientists to

develop an airplane capable

of carrying a person were underway

in Europe and America, two brothers from

Dayton, Ohio, were quietly,

doggedly, and methodically

teaching themselves everything there was to

know about flying, and

inventing all the rest as the need arose. What

exactly drove the Wright

brothers to embark on the odyssey

that led them to Kitty Hawk is not at all clear,

and even definitive

biographies like Tom Crouch’s The

Bishop’s Boys have trouble penetrating those two

inscrutable minds. And that’s just the way they would

have wanted it.

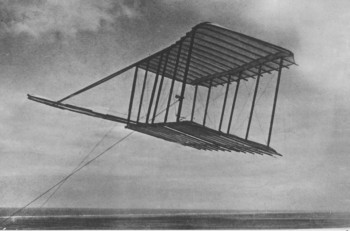

This 1900

glider, in a wind from the left, was moored by a wire below

and raised or lowered by a wire (not visible in the photo)

that pulled the forward elevator up or down.

Wilbur was born

in 1867, and Orville four years

later the third and sixth of seven

children born to Milton and Susan

Koerner Wright. Milton was a

minister in the United Brethren

Church, an evangelical Protestant

denomination, and the family moved frequently until

Milton was named a bishop in the church

and the family settled in

Dayton, Ohio. In childhood and throughout

their lives, Orville and Wilbur

were constant companions (in

‘Wilbur's words, the brothers “lived together, played

together; worked together, and, in fact, thought together”)

and displayed many of the Yankee characteristics of their

parents and forebears: an inner-directed Spartan strength

and a clear-eyed, determined outlook on the world and on

life. Neither brother finished high school. though they were

both insatiable readers and tinkerers. The Wright brothers

tried their hand at several enterprises, including

publishing newspapers and running a printing shop, hut

without success.

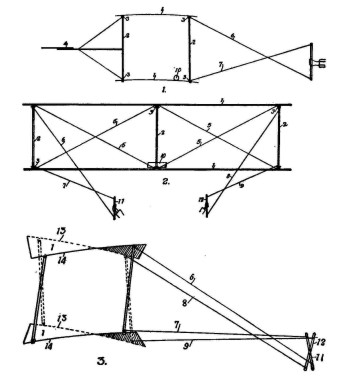

Wilbur's drawings of the 1899 Kite, the

Wright brothers' first aeronautical experiment

In 1892, America was in the midst of a bicycle craze and the

brothers established a bicycle shop in Dayton that proved

financially successful. They manufactured some bicycles

under their own brand name, including one they called the

Flyer. During 1896, the Wrights read about the death of Otto

Lilienthal and they became intensely interested in the

question of flight. They collected all existing information

on flight, writing to Octave Chanute and Samuel Langley at

the Smithsonian, beginning an active correspondence with

these men that was to last for years. Chanute (who regarded

himself as a kind of international clearinghouse of

information about flight) was particularly generous.

The Wrights designed a glider, strongly influenced by

Chanute’s design, and decided that their aircraft would not

be as difficult to fly as Lilienthal’s glider, but neither

were they going to be passive passengers on a an inherently

stable aircraft. They devised a method to control an

aircraft in flight that involved twisting a Chanute design

in a technique called “wing warping.”

With a pilot (in this case,

Oiville) warping the wing, the glider banked as expected,

but would “slip” to the side and

invariably crash sideways into the sand.

There are many

stories about how the Wrights came upon wing warping, but

the fact is that the technique was not new, and at least one

American experimenter, E. F. Gallaudet, made use of it in

kite tests near New Haven, Connecticut, in 1898. With their

customary thoroughness, the Wrights also wrote to the U.S.

Weather Bureau to find out the best place to test aircraft.

On the basis of that information, they selected the Kill

Devil Hills sand dunes outside Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, a

fishing village on the Outer Banks, a thin peninsula that

jutted out into the Atlantic and enjoyed strong and

relatively constant winds.

In 1899, they tested a scale model of a glider in Dayton,

and by the late summer of 1901 they were ready to test-fly

their first full-size glider at Kitty Hawk. The trips to

Kitty Hawk were arduous; a great deal of material had to be

brought along, some in pieces that would be reassembled on

site. The conditions were difficult and the pair’s resolve

and fortitude were tested to the limit by heat, mosquitoes,

storms, cold gale-force winds, and isolation.

The solution was to

place a double rudder in the rear so the glider would “bite”

the wind when it banked into a turn, as it does here as

Wilbur banks the glider in the 1902 tests. The pilot is

still lying down in order to cut down wind resistance

(“drag”).

The locals

liked the Wrights and the Wrights liked them, but the

brothers’ natural reticence caused some people to regard

them as secretive—some believed that was why Kitty Hawk was

chosen as a test site in the first place. But at this stage,

the Wrights were not at all hesitant to share their findings

with fellow researchers. In fact, in the midst of their

experiments, Wilbur accepted an invitation from Chanute to

report on his and his brother’s experiments at a meeting of

the Western Society of Engineers in Chicago, and many of the

people Chanute kept bringing to Kitty Hawk to assist them

were, the Wrights well knew, doing research of their own.

The craft “flew” (it actually glided) well enough, but with

thirty percent less lift than the Wrights had calculated.

They returned to Dayton and built a larger craft with a

front horizontal rudder (called a “canard”), and returned to

Kitty Hawk in July 1901 to test it. The performance was

improved and the control bugs were worked out, but the

Wrights were perplexed about why their calculations were

still off. Their response to this was unique and would he

reason enough to regard the Wrights as the first to fly.

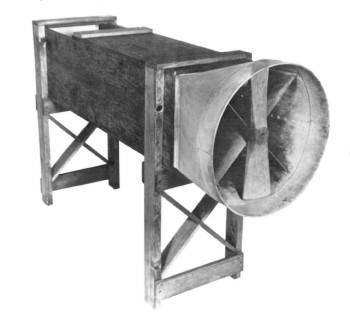

They constructed a wind tunnel in the rear of their bicycle

shop and conducted precise tests of different wing sections.

The tunnel was only six feet long by sixteen inches square,

with a glass window in the top panel to allow observation. A

steady fan driven by a small gas engine blew air through the

box at a steady twenty-seven miles per hour ), and inside,

balance and spring scales measured lift and pressure on a

variety of airfoils. In these experiments, the Wrights

raised aviation experimentation to the level of serious

engineering (and were thus more firmly in the tradition of

Cayley and Langley than anyone else had been for over a

century).

These tests were made in November and December 1 901; they

collectively represent one of the most important phases in

the early history of flight. The Wrights discovered that

much of the published data on airfoils was incorrect or had

ignored important elements of an airfoil in flight. They

arrived at a clear idea of how the centre of pressure moves

about an airfoil in relation to the angle of attack and as a

function of the camber. And they knew what the control

surfaces would need to be able to do if the flight was to be

controlled by the pilot. After testing two hundred different

wing surfaces, the brothers used their newly gained

information to design Glider Number 3. It was equipped with

a forward elevator wing and a rear fixed double fin that was

later made adjustable, with its controls connected to the

wing-warping controls for the main biplane wing section.

They returned

to Kitty Hawk in September and tested their new machine in

more than one thousand glides. It not only performed well,

it performed as predicted. It was only now that the Wrights

felt they were on the verge of succeeding in creating a

powered airplane. They filed for a patent in March 1903, and

turned their attention to the last hurdle: turning their

glider into a flier.

The decade from the December 1903 flight of the Flyer at

Kitty Hawk to the outbreak of World

War 1 in August

1914 was an extraordinarily busy one in the

development of aviation. Looking

at the aircraft being built in

1913 and comparing them to those

built in 1904, it is difficult to

believe that only a decade had

passed. Airplanes like Louis

Bechereau’s Deperdussin Racer and

Geoffrey de Havilland’s B.S.1,

both produced in 1913, were built with

enclosed, metal fuselages

that used “monocoque” design:

instead of just the frame, the entire fuselage supported the

plane’s load. These planes are recognizable early

versions of planes produced thirty

and forty years later, while the

spindly frames of the Wrights’ airplanes and the

early flying machines were by that

time only relics.

The Wright

brothers had clearly uncorked a torrent of industry

and creativity that had simply

been waiting for some indication that the prospect of flight

was not hopeless.

But if the Wrights were the spark that ignited the

enterprise, there were other forces at

work that drove it to a

fever pitch. One was the giddy optimism that characterized

the opening of the new century.

True, the twentieth century’s ambivalence about technology

was born in its very

first decade, but in the face of the many advances

from 1900 to 1914, it really began to look as if

technology could and would make just about anything

possible.

The Wrights played

a large part in the forming of

this attitude: the remoteness of

their experiments gave fuel to the

claims made by such prestigious

publications as The New York Times

and Scientific American that their

flights were a hoax. One can

imagine these publications being

much more careful afterward in

their scepticism about any

scientific and technological claims.

Yet, there was the equally powerful sense

that a war was coming, and

that one result of the

industrialization of Europe would

be an improved ability to conduct

armed conflict. What role aviation

would play in the theatre of war was not clear even to the

most visionary planner but

there was no doubt that aircraft (both heavier

and lighter than air) would be exploited by

combatants to the fullest

and that command of the sky could possibly

be a decisive factor in any

war. Military strategists who

prepared for possible invasions across natural barriers

such as the English Channel

or the Alpine mountains had to

rethink their defences in the light of aerial

warfare of unknown

effectiveness.

Behind all the

hoopla of the races, the feats,

the records, the stunts, the

glamour and derring-do—all the

romance of early aviation—were calculating minds

fully aware (or aware enough to take

anxious notice) of the military potential of flight.

In the decade between Kitty

Hawk and the outbreak of World War

I, one can summarize the history of

aviation very simply: while the Wrights and Curtiss

were slugging each other senseless

in court, the Europeans

slowly took the lead in aviation. The Wrights won

many of their court battles, but

lost the war for supremacy in

the air.

They enjoyed two

crowning moments in the decade

following Kitty Hawk: their exhibition in France

and their test for the Army at Ft. Myer. But they

allowed many opportunities

to slip by: while Curtiss was winning

prizes for aviation feats he was

performing years after the

Wrights had passed that level of technology, the brothers

were too proud or secretive

to claim any prize; while Curtiss

was winning races that the Wrights could

have won handily, the

brothers would not consent to enter any

contests; while Curtiss was

gaining fame participating in

aerial exhibitions and air shows, the Wrights regarded

them as circuses unworthy

of their talents; while Curtiss was

forming productive and useful alliances with a wide range of

people—from Bell and the Smithsonian to August Herring,

Octave Chanute’s old assistant to Henry Ford and his

high-priced patent lawyers—the Wrights steadfastly rebuffed

any offer of collegiality (including from Curtiss) and

preferred to go it alone; while Curtiss developed new

technology as quickly as it became available—he abandoned

wing warping when it became clear ailerons were a superior

means of lateral control; he developed wheeled

undercarriages when they were shown to be preferable to

skids; and he experimented with different engines and

configurations

Wright wind tunnel

The Wrights

never strayed far from the basic design configuration they

inherited from Chanute; and while Curtiss developed the

entire field of naval aviation, developing seaplanes that

could consider attempting to cross the Atlantic Ocean, the

Wrights entered the field belatedly and half-heartedly.

But for a

moment, the Wrights were alone at the pinnacle of the

mountain, and their country and the world paid them homage.

Wilbur died of typhoid fever in 1912, but Orville lived

until 1947. Orville was honoured late in his life for the

contribution he and his brother had made to flight, but he

certainly must have wondered what might have been had Wilbur

lived. Publicly he blamed Curtiss and the Smithsonian for

everything (even Wilbur’s death), but Curtiss retired from

active involvement in aviation in 1921 and turned to real

estate speculation in Florida until his death after an

appendectomy in 1930. So it was hardly the case that it was

all Curtiss’ fault. Typically, Orville never voiced any

regrets for letting the dominion of flight slip through his

fingers. Still, one wonders.

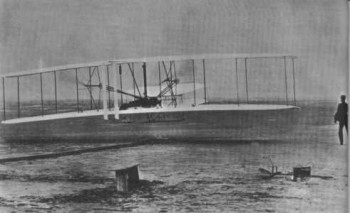

Kill Devil Hill, December 17, 1903

After the Wright brothers’ successful glides in the summer

of 1902, it was time to add an engine and propellers to the

machine. Typically, however, the Wrights did not simply add

a power plant to their glider; they redesigned the entire

machine and integrated the propulsion system in a

technically well-designed machine. The added weight of an

engine meant they could increase the camber (which would

result in the centre of pressure behaving about the same as

it did for the glider), and enlarge the wing to a forty-foot

wingspan and a surface area of 510 square feet for the two

wings combined.

The machine—which they called the Flyer I (only later was

its name changed to the Kitty Hawk)—retained the glider’s

front canard-design elevator and the movable rear rudder.

The plan was to place the engine on the lower wing, next to

the pilot who would, as was the case with the gliders, lie

prone on the lower wing. The propellers would be “pusher”

(meaning, pushing the machine from behind the wing, as

opposed to “tractor,” which means pulling the machine in

front of the wing) and would turn in counter-directions. As

they had done with the wings, the Wrights had tested and

perfected the propellers in their wind tunnel and greatly

improved their efficiency. Unlike the gliders, the Flyer

could not be launched by leaping from a dune or by running

down a hill; it would then be only a powered glide and not a

real flight. They designed a launch mechanism that consisted

of a single track on which ran a simple flat car that the

aircraft was placed upon.

The car would be propelled by the aircraft’s propellers, and

when take-off speed was attained, the airplane would simply

lift off. The Wrights calculated that they would need sixty

feet of track (and that is what they brought). The Wrights

had put off the question of the engine, hoping that the

strides being made in the automotive industry would produce

a light and powerful engine they could use. But no such

engine was forthcoming and finally they attacked the problem

head-on and designed their own engine with the help of their

machinist, Charles Taylor. The engine just barely met their

specifications, but they decided not to postpone testing it.

They did not arrive at Kitty Hawk that year until September

26 and were not ready to test their machine until winter

was already setting in.

It was too cold even for Chanute, who had waited patiently

as long as he could. After many delays and repairs, on

December 14 the Flyer seemed ready. The brothers, aware that

they were about to make history, tossed a coin to see who

would have the honour of the first flight. Wilbur won. On

the first attempt, however, the elevator was set low and the

craft ploughed into the sand at the end of the track,

damaging the aircraft. After three days of frantic repairs

and threatening weather, the Wrights were ready for a second

try. They raised a flag signalling the crew of the

lifesaving station that they were ready, and when a small

group arrived, Orville took his turn on the lower wing. At

10:35 A.M. on December 17, before several witnesses from the

weather station, the Flyer took off into a

twenty-one-mile-per-hour (34kph) wind. Wilbur ran alongside

the aircraft, keeping the right wing from dragging in the

sand but being careful not to assist the plane down the

track; they wanted this to be an unassisted take-off.

Sensing that they would be successful on this day, they had

set up their cumbersome glass-plate camera and aimed it at

the end of the track. They instructed one of the witnesses,

John T. Daniels, to snap the shutter as the plane left the

end of the track. Daniels took one of the most famous

photographs in the history of aviation, possibly in the

history of all of technology. It shows the Flyer lifting off

with Orville aboard, and Wilbur off to the side having just

run down the track alongside. The Flyer flew for twelve

seconds and landed in the sand 120 feet away.

Wilbur is seen here aboard the Flyer (now outfitted with

motor and propellers) as it dips and runs aground on takeoff

during its first

test on December 14, 1903. The damaged elevator required

three days to repair.

The brothers quickly placed the

Flyer on the launching car for another

flight. This time Wilbur

piloted the craft and it flew

almost two hundred feet before

landing gently in the sand. In

all, they conducted four

flights, alternating as pilots, with the

best flight the fourth: 852 feet in fifty-nine

seconds. After the fourth

flight, a gust of wind overturned the

aircraft and damaged it beyond

quick repair. The brothers

knew they would be returning to

Dayton. They ate a leisurely

lunch, then went into Kitty

Hawk, called a few friends to report on their

success, and sent a telegram to

their father: “Success four flights

Thursday morning all against twenty

one mile wind started from Level with engine power alone

average speed through air thirty one miles longest 57

seconds inform Press home Christmas. (signed) Orville.”

Contrary to legend, the reaction of the press to the

historic flight was not a deafening silence. The Dayton

Evening Herald reported the flight the next day on the front

page, and the Virginian-Pilot was careful to point out in a

sub-headline that no balloon had been attached to the

aircraft. Garbled accounts appeared on the front page of the

New York Herald, but there was little follow-up and many of

the sporadic reports that appeared during the first two

years after Kitty Hawk ridiculed the Wrights’ claim by

adding facetious exaggerations to the account. The first

full, serious, and accurate account of the Wrights in flight

appeared in the January 1, 1905, issue of Gleanings in Bee

Culture, an apiary journal, written by the publisher, Amos

I. Root. But the Wrights were not people to waste time. On

their return to Dayton, they immediately set to work on the

Flyer 2. incorporating all that they had learned in the

Carolina dunes. It looked like the first machine, but had a

smaller wing surface and a gentler camber. Most importantly,

it had a more powerful engine.

The brothers rented a ninety-acre (36ha) farm outside of

Dayton that became known as “Huffman Prairie” (after the

owner) and tested their new machine there. On September 20,

1904, Wilbur flew the Flyer 2 in a complete circle and

returned to his starting point and landed. This was the

flight Root witnessed and described, and in the minds of

some aviation historians, this flight and the others

conducted at Huffman (and not the four Kitty Hawk flights)

deserve to be considered the beginning of the age of flight.

(Others point out, however, that these take-offs were not

unassisted: to compensate for the lighter winds, the Wrights

launched their aircraft at Huffman with a weight-and-derrick

launcher.) The best flight of the season, four circles of

the field, lasted over five minutes.

In the summer of 1905, the Wrights tested an even more

improved machine, Flyer 3, as always, in full view of

onlookers and inviting the press to important tests, which

they rarely attended. The aircraft had an even smaller wing

surface but the same camber as the 1903 machine. This time

the machine flew beautifully, and many of the more than

forty flights conducted were limited only by the amount of

fuel the aircraft could carry. The plane could take off and

land with minimal adjustment, and the elevator and rear

rudder, pushed out farther from the wings, gave the pilot

almost complete control of the aircraft in flight. The

longest flight of that summer was over a half hour, and the

aircraft could circle and fly figure eights easily. This

aircraft, the Flyer 3, is often referred to as the first

practical aircraft in history.

In 1905, the brothers sensed trouble when their patent

application of two years earlier was delayed. The U.S. War

Department was unenthusiastic about their proposal to build

airplanes for the Signal Corps, and they kept hearing

rumours that competitors were copying their designs. The

patent (for wing warping) was granted eventually in 1906,

and the U.S. government eventually came around, but the

challenge from rivals—one in particular: Glenn

Curtiss—proved to be one hurdle too many.

|