|

|

|

Harry

Hawker

Harry George Hawker.

Harry George Hawker, the second son of a Moorabbin blacksmith of

Cornish blood was born in a small rented terrace cottage in

Wickham Rd., on January 22, 1889. When he was born, John King

and his wife Deborah, the original settlers of the Moorabbin

district were still living on the land which they had pioneered

as the first white settlers to take up residence.

Australia itself had only been established 101 years and already

there was a new era which in turn heralded a crisp challenge to

a coming generation to face up to the machine age. Harry Hawker

although still a schoolboy was ever eager to accept that

challenge so much so in fact that he disregarded the essential

pre-requisite of a sound primary education.

His first tuition was gained at the Worthing Road State School,

Moorabbin, but the depression coupled with his own lack of

interest in basic education saw him move to another three

schools in the six short years of learning that represented the

only schooling he was ever to enjoy. The fourth and final school

that he attended was at Brighton and it was from here that this

lad with the great mechanical mind finally decided to abscond

from school for all time to accept five shillings per week from

the motor firm of Hall and Wardens at a time when the adult wage

had reached an all time high at six shillings per day. But to

Hawker a paid job in the field of mechanical engineering was all

that mattered.

Moorabbin State School at Worthing Road, C1910.

He became known through the local districts as a man who could

set the most stubborn of motors in action within a very short

space of time. The monetary reward was excellent but success as

it was later to be proven always brought restlessness to Hawker

who was ever eager to improve upon his immediate lot.

The automobile trade has been a valuable one for him. It had

been the means of gaining jobs outside his normal employment

hours. He had no fears about leaving the trade as he could

always come back to it, but to become an aviator in his own

country – the thought was almost laughable.

In 1910 an aviation event which stirred the air-minded people of

the whole world – caused a restlessness amongst the keenest of

the keen that was hard to overcome. It was the London to Paris

air race. In London the great pioneers of world aviation, first

known as aeronauts and later as aviators, assembled to prepare

for the first massed attempt at crossing the English Channel by

heavier than air machines. England became the centre of

attraction of thousands of would-be British flyers, including

many Australians, who realised the hopelessness of waiting for

the new mode of adventure to reach their own shore.

Hawker believed that in England he would soon learn to fly and

the young man of scarcely 22 years of age left his native shores

hoping of success in the new sphere and perhaps at the same time

wondering if he was doing the right thing. With three other

Australians, Hawker arrived in England in May; and in the spring

of 1911, he felt the need for a holiday more urgent than of the

task of looking for work. However when after a short rest he

foresaw the difficulty involved, he regretted having taken the

break, as the employment position was not what he believed it to

be. As he was to find out later the problem that facing him was

a general one which also confronted the English mechanic as well

as those from various parts of the globe.

The position was created by the enthusiasm of England’s own

youth who were already working as motor mechanics and were

lining up at airport employment offices eager to break into

newer mechanical field. Anyone without references just did not

stand a chance and Hawker, 10,000 miles from home, had not the

word of one referee in writing. Then as he moved from one

workshop to another, first in the aircraft industry and then in

the motor car trade, he began to realise what his neglect was

costing. Without documentation, he couldn’t even get a trade

test let alone a job.

One of his main disadvantage s was that by this time he was an

adult and as such his services were more costly to the employer.

As an ‘unknown’ he was considered a risk and what was needed was

someone to explain, how his ability had always kept pace with

the remuneration he received for his services at home and, with

a pool of employers only too anxious to place him on the

payroll. But towards the end of July 1911, when he had fully

made up his mind to return to Australia, he received an offer of

steady employment from the Commer motor firm and decided to

postpone the plan.

By February 1912, things were again improving through a new job

at the Mercedes Company at two and a half pence an hour more.

Next thoughts were ‘should I go home as planned or spend the

money I have on flying lessons?’ Later an invitation came to

visit the foreman of the Austro-Daimler Company. This led to a

better position again than his previous one, although he had

still to break into the somewhat exclusive aircraft industry.

The temptation to return to Victoria as a top rate mechanic

presented itself but was overwhelmed by another urging him to

stay on until the opportunity to enter a cockpit presented

itself. That opportunity came to him per medium of the Sopwith

Aviation Company at Brooklands early in the summer of 1912 after

he had been advised by a friend to call on Mr Sigrist at the

company’s airport hangar. Actually the Sopwith Company had a

work force of 14, and Hawker became the fifteenth member. The

business of the company centred around a flying school and the

building of the Howard Wright biplane, but to Harry Hawker it

was the opening of a complete world of aviation.

Harry Hawker was employed as a mechanic with the small Sopwith

company and scarcely had he been placed on the payroll when he

began lessons in flying as a pupil of Sopwith, his employer. He

paid for his tuition from £40 which he had managed to save from

wages during the time he had been employed by the various

automobile manufacturers. Hawker was an outstanding pupil who

was ready for solo four days after receiving his first lesson.

Here was a natural pilot who had learned so much from merely

watching others take their machines into the air and land them

at Brooklands that everyone came to him quite readily, and in

September he was granted his flying ticket. Then within a matter

of days he was giving instruction to other newcomers to the

craze and gaining success as a tutor. But like all routine

practices, that of flying instructor soon became a bore to Harry

once he had recouped the cost of his own lessons, and he was

again in search of adventure, this time in the form of

competitive flying.

The British Empire Michelin Cup was his first attempt in this

field. Taking advantage of the calm atmosphere Hawker glided his

machine gracefully but carefully in order to maintain the

greatest possible altitude, then, drifting into a side slip, the

plane into a banking exercise to the renewed sound of the

clattering airscrews and motor, only to be silent again and

repeat the previous act.

The Sopwith Company men had gone to the trouble to rebuild the

American Burgess-Wright biplane which had had a twin propeller,

and to modify it to their own design in order to meet the

competition requirements. He had to stay aloft as long as was

humanly possible. After eight hours and 23 minutes after

take-off the casual, smiling pilot lifted his frame from the

cockpit as the new duration flight champion. He had gained the

Michelin Cup No 1 and won the £500 prize money. Hawker had

shattered the record.

Despite the fact that Hawker had left school at the age of 12,

he managed to gain his ambition to become an aviator. After

suffering the hardships that meet the technically unqualified he

reached another goal, but still his mission was far from

complete in that he wanted to fly his machine high above the

trees and farms that flourished in his native soil in the Parish

of Moorabbin.

Hawker was fully convinced that the aeroplane had a definite

future but there was still a lot of others, important people

like heads of government and those with capital to finance

production who were sceptical about the whole idea. Too many

ordinary people, even among his own admirers, regarded the

machine as something of an aerial bicycle on which the rider

performed his feats in the sky instead of at a velodrome.

With the offer of prizes now being made Hawker saw the means of

making flying a paying proposition. Geoffrey De Havilland’s

endurance record of 10,650 feet was his first target in this new

plan to prove the ability of his machine. The £50 offered by the

Brooklands Automobile Club as a prize to anyone who could go

higher provided the incentive to meet the challenge.

Hawker climbed into the Tractor Biplane (another of Sopwith’s

products) and the aircraft rose into the calm wind of the day

and circled above the heads of the crowd. When it finally landed

there alighted the new solo height champion, Harry Hawker, with

11,451 feet to his credit. But it was not good enough for Harry.

He was soon to be seen taking off with a passenger whom he took

higher than he had gone solo. He later followed up by taking two

passengers to another record breaking effort, then in July of

the same year four men rose to a height of 8400 feet with Hawker

again at the controls.

That was good enough in any man’s book, it had proven beyond all

doubt that given the correct design and power to match it, an

aircraft could extend itself beyond the one-man carrying stage

and lift a good number of passengers safely having at the same

time ability if required to rise in inclement weather to the

safety of a higher altitude.

More than two years passed since his arrival in England and now

that his mission had been achieved Harry George Hawker felt the

need to return to his native Australia and the Parish of

Moorabbin where he had planned to make his first flight in his

own country. He had funds – enough to buy his own aircraft to

crate back to Melbourne, pay his fare and keep himself until

orders for machines from Australians could perhaps set him up in

business in Victoria.

Hawker was met by friends soon after the ‘Maloja’ had berthed

and was taken to the St Kilda Town Hall, where he was greeted by

the Mayor of St Kilda and citizens and councillors from St

Kilda, Brighton and Moorabbin. After the reception the aviator

had one thought uppermost in his mind and that was to again

experience the thrill of flight, but first of all the Sopwith

was scheduled for a ground display at the C. L.C. Motor and

Engineering Works in Melbourne. Then came the long awaited

flight over Melbourne’s suburbs, the first of which began from a

paddock in New St., Brighton, as a solo test flight, but

eventually took in an aerial display over the whole of the

Parish of Moorabbin, which included the City of Brighton and the

Shire of Moorabbin.

The first flight was intended to be something of an unofficial

take-off and landing in the shape of a ‘circuit and bump’ affair

but by the time that Harry had carried out a ground run to check

his ‘revs’ people were beginning to gather in anticipation of a

flying performance and Hawker was not the kind to ignore their

interest. Climbing to about 1000 feet he circled the near

vicinity, intending to land, only to see the pupils of the

Sandringham State School in the south assembling in the

playground to greet him, so with a swift bank at about 200 feet,

the plane swooped low over the school with the pilot’s arm

clearly visible returning the waves of the teachers and the

pupils. Further south again, the Mordialloc State School was

ready and received the same exchange of greetings.

Never was a welcome more sincere and never was one more

appreciative. There was not a school nor a home nor a farm or

business premise where the occupants did not turn out in force

to greet the successful aviator. What was to be a five minute

circuit and bump test flight ended after 50 minutes of furious

waving.

After the exchange of greetings came the business side of the

adventure and the triumphant airman found no difficulty, as he

turned his attention towards barnstorming, in bringing in

passengers at £20 at a time.

On February 7, 1914 a Saturday, Hawker had signed himself up to

a promoter, Albert Soulthorpe, of Swanston Street, Melbourne, to

give ‘a public display of aviation at Caulfield Racecourse or

other suitable grounds’. Proceeds were to be equally divided

between the promoter and the aviator. Again the Moorabbin people

turned out in full force, but only to become insignificant in

their numbers against the thousands who arrived from other parts

of the metropolitan area and beyond.

Harry Hawker's plane the Tabloid Sopwith on the Elsternwick Golf

Course. In the foreground is Harry's father, George. 1914.

The following Friday was in fact Friday 13, but it was not

regarded as unlucky by Harry and his intended passengers. It was

a V.I.P. day for Hawker and the plane with ‘SOPWITH’ boldly

printed along the fuselage. One passenger was the Minister for

Defence, Mr Millen, who thereby became the first Australian

Defence Minister ever to go aloft. He was of course suitably

impressed, but recorded no comment that was strong enough to

bring forth aircraft orders on behalf of the Commonwealth

Government.

Hawker could not wait. He had to be back in England in time for

the flying season which would reach its height in June, and

after a few short weeks in Australia he was off on the return

journey. At Caulfield everything was back to normal, although it

has since been noticed that there is a bent lightning conductor

on the tower of a convent, which a number of people say lost its

straightness when Hawker’s Sopwith struck it on a landing

approach.

The Sopwith ‘Tabloid’ as the plane which Hawker brought to

Melbourne was known, was produced at the Kingston factory of

Sopwiths for the first time in November 1913, and in bringing it

to Australia, Hawker was giving his people the opportunity to

see the very latest in aircraft design. But there was something

very special about the ‘Tabloid’ in that it was to prove a point

that eventually led to the biplane being produced in preference

to the monoplane for a number of years to follow. It was Hawker

who proved by looping the loop in the Sopwith ‘Tabloid; that in

the long run biplanes were more manoeuvrable and (when properly

designed to the correct wing stagger) were also faster.

It was largely due to the ultimate proof presented by Harry

Hawker that World War I was fought with biplanes rather than

their single winged counterparts, monoplanes. But in his efforts

to prove this theory, Hawker suffered a permanent injury when

looping the ‘Tabloid’ with the motor idling. In one of a series

of loops designed to test the machine to its utmost, the

airframe stalled and went into a tailspin to land with a clumsy

thud among the trees adjacent to the aerodrome. Harry suffered a

back injury which although only appearing to be slight at the

time, gradually became worse during the few years of life that

followed.

But the war was close at hand and Hawker became the chief test

pilot of the Sopwith group. This was his wartime occupation and

three months before the cessation of hostilities the name of

Harry George Hawker appeared in the Birthday Honours list as a

Member of the Order of the British Empire. The citation referred

to his work in the development of a number of aeroplanes such as

the ‘1 ½ Strutter’, the ‘Camel’, the ‘Pup’, the ‘Triplane’, the

‘Dolphin’ and the ‘Snipe’.

Mr Tom Young, the Mayor of Moorabbin, Cr H Stevens, Mr Arthur

Saunders, Mr Harry Hawker, Mr Tom Sheehy, Messrs Bill and Bob

Chamberlain and Mr Leo Whelan with a propeller believed to come

from plane which Hawker flew at his demonstration over Caulfield

race course, 1966. Leader Collection.

In the ‘Atlantic’ a Sopwith plane, Hawker set out with Commander

Grieve in Newfoundland to fly the Atlantic. The ‘Atlantic’ was a

single-engine biplane with 350 horsepower Rolls Royce engine

weighing 850 lbs. The all up weight of the plane was 2850 lbs

and it had a maximum speed of 118 miles per hour.

Frustrated by bad weather, which delayed the flight from the

very beginning, Hawker and Grieve decided to chance the elements

on May 18, 1919, after a seven weeks’ wait for improved weather

conditions. Before leaving Hawker saw reason to exchange the

four-bladed propeller for one with two blades, and after

take-off he also dropped the under cart, the idea being to

reduce the load as well as cut down the air resistance. But

predictions went astray and the inclemency of the day sent winds

from the north instead of the anticipated north-easterlies. Thus

they were blown 150 miles off course; ‘fog, cloudbank and ice

formation on the wings added to the dilemma of the trip’; then

an over heated radiator forced them to fly in search of a ship

with a view to ‘ditching’ the machine. A two and a half hour

search found the ‘Mary’ which was bound for Lentland Firth from

the Gulf of Mexico, and Hawker set down on the sea about a mile

in advance of the ship and awaited rescue.

There seemed to be a jinx on Hawker as far as prizes offered by

the Daily Mail were concerned. Just as misfortune had cost him

the chance of winning the prize for the flight around England in

earlier years, history had repeated itself in the Daily Mail

£10,000 Atlantic offer. Hawker might well have waited for better

weather conditions when he arrived at the flying base near St

Johns aboard the S.S. Digby had it not been for the British

pride that was part of his make up. Two days before he decided

to set out on his venture he had been informed of three American

flying boats, the NC1, 3 and 4, having left Newfoundland and

arriving at Portugal. He accepted the American rivalry as a

challenge and took off prematurely, only to become reported as

‘missing at sea’ while the American NC4 in the meantime went on

to claim and win the £10,000.

The evening paper on Sundays was the ‘Sunday Telegram’, and

through its columns England learned of Hawker’s safety. The

‘Mary’ had picked up Hawker and Grieve, but had left the Sopwith

to the mercy of ‘Davey Jones’, and perhaps it was adding insult

to injury that the Americans picked up the floating ‘Atlantic’

and carried it aboard ‘Lake Charlottesville’ to Falmouth. In the

meantime Hawker was transferred to a British destroyer as a

guest of the Royal Navy. Leaving the ship with it reached

Scotland, he and Grieve began their train journey to London

which began with massive crowds turning out to cheer them on

their way. Later in May both the airmen were called to

Buckingham Palace where King George V, a keen admirer, presented

them with a new award, as jointly they became the first

recipients of the Air Force Cross.

But with the war over there were difficult times ahead for the

Sopwith Company, which in 1920 went out of business. Hawker’s

name came into prominence when, with the aid of his former

Sopwith colleagues, the H.G.Hawker Engineering Company was

formed. Hawker filled in his time during the next few months by

participating in motor racing events as well as flying. But on

July 12, 1921, the tragedy that shocked an empire came suddenly

when a Nieuport ‘Goshawk’ in which Hawker was flying caught fire

in the air. Hawker remained skilful to the end. Although badly

burnt he managed to extinguish the fire and was attempting a

forced landing when the plane hit the ground and threw him clear

of the machine; but with the burns and possibly because of the

added injuries he received in impact. Hawker lived for only a

few minutes.

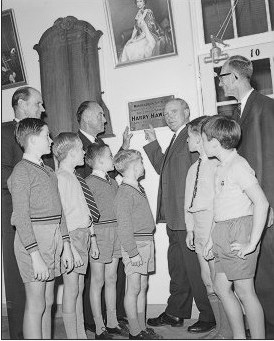

Unveiling a plaque to honour Harry Hawker at the Moorabbin

Primary School. Cr D Blackburn (left) Mr Wheeler of Hawker de

Havilland, Tom Sheehy and Mr Shannon with Alan Biggs, Graeme

Wilson, Robert Wheelar, Guy Coape-Smith, Robert Ellis and David

Clottu, 1966. Leader Collection.

|

|

|