|

GeeBee

Z

SEPTEMBER 7,

1931. Eight racing aircraft, some of the fastest land planes

in the world, were lined up for the start of the Thompson

trophy race at Cleveland, Ohio. The field consisted of

Lowell Bayles in a Gee Bee Model Z, Jimmy Doolittle in his

Laird "Super Solution", Jim Wedell in a Wedell-Williams

Special, Ben O. Howard in his Howard "Pete", Dale Jackson in

a Laird "Solution", Bill Ong in a Laird Speedwing, Ira Eaker

in a Lockheed Altair, and Bob Hall in a Gee Bee Model Y. The

Thompson was a ten lap race of 100 miles and was the climax

of the National air races.

As the

starter's flag dropped, all conversation was lost in the

roar of the eight powerful engines as the entries blasted

toward the first pylon one mile away. Doolittle was the

first pilot to make the turn but soon his "Super Solution"

began trailing black smoke from a broken piston. Gamely he

tried to hold his position. On the second lap, Bayles in his

Gee Bee Z, "City of Springfield", took the lead. Dale

Jackson had a narrow escape from tragedy as he brushed a

tree, but he continued to race. Bayles continued to extend

his lead. On the seventh lap. Doolittle was forced to

retire. Bayles roared across the finish line at an average

speed of 236.2 mph, culminating a week of triumphs for the

Gee Bee team. Bob Hall finished fourth in the Model Y at a

speed of 201 mph. The Gee Bees had nearly dominated the 1931

National air races and the Model Z had won every contest in

which it was entered. The Granville brothers, the guiding

spirits of the Gee Bees, returned to Springfield,

Massachusetts, at one of the high points of their careers,

unaware of the rocky road that lay before them in the years

to come.

Mention the

Gee Bee racers and most people recall only the many

accidents that befell these aircraft and their pilots. Over

the years, various articles have pictured these craft as

"killers", "the most dangerous aircraft ever built", etc.,

and the inaccurate impression has been given that the

Granville brothers were "backyard builders", simply adding

more and more horsepower to inherently unstable airframes.

Actually several competent engineers were always on their

staff, wind tunnel research was utilized and their

construction methods were always of the highest calibre.

Some crashes did occur through human error or on aircraft

that had passed from the influence of the Granvilles.

Unfortunately, it seemed that the Granvilles bore the brunt

of criticism for factors beyond their control. Irresponsible

members of the press equated the name "Gee Bee" with

spectacular crashes.

The children

of Wilfred and Belle Granville, Zantford (Granny), Robert.

Tom. Edward. SIark and sisters Pearl and Gladys, were

originally from Madison, New Hampshire. Granny, the oldest

child, was a self-taught automobile mechanic with an

eighth-grade education who had an affinity for anything

mechanical and thrived on hard work. When Granny was 17 he

moved to the Boston area where he took a job selling

Chevrolets. A year later he established an auto repair

business in Arlington where he sold Chevrolets and did

service work. At the age of 20, he appeared at the East

Boston airport where he exchanged his services as a mechanic

for flight instruction.

Leaning more

and more toward aviation, in 1922 Granny summoned his

brother, Tom, to run the auto repair business while he went

to work as a mechanic with the Boston Airport Corporation.

Deciding to go into business for himself. he established

Granville Brothers Aircraft and was joined shortly

thereafter by his three remaining brothers. Granny's

mechanical sense told him that he could improve upon the

designs of many of the craft on which he was working. He and

his brothers spent their spare time building a side-by-side

biplane powered by a 55 hp engine that they had bought for

$500. Known as the Model A, it had its first flight at 5:30

a.m. on May 3, 1929.

Searching

for adequate facilities to manufacture their biplane, the

Granvilles contacted the chamber of commerce of Springfield,

Massachusetts, on May 17, 1929, and on July 6 finalized

plans to locate at the airport there. Hoping to attract

backers to finance production of their Gee Bees, they

entered their first air meet at Springfield on July 10. Here

they met the four Tait brothers, James, Harry, Frank and

George, owners of Springfield's biggest ice cream and dairy

business, as well as developers of the Springfield airport.

George Tait handed Granny a check for $1,000 and told him to

come back after he had put "a real engine" in their plane.

Returning to Boston, they purchased an Armstrong Siddeley

"Genet" engine of 85 hp which greatly enhanced the

performance of their prototype. A few weeks later, Granville

Brothers was incorporated, building planes in an abandoned

dance pavilion formerly named the Venetian Gardens at the

Springfield airport

Among the

first workers on their staff were Albert Axtman, Austin

Savary and Harry Jones. A secretary was hired and three

college educated engineers were added to the rolls. These

were the "Three Bobs", Bob Hall, Bob Ayre, and Bob Dexter,

all of whom went on to successful careers in aviation.

Fitted with a Kinner K-5 engine, nine of the Model A's were

built and sold before the depression-plagued market dried

up.

Hard times

descended on the Granvilles. Ed and Mark rented an attic

room and lived on beans which they purchased by the case. In

the fall of 1929, few men had the money to purchase anything

as frivolous as a personal airplane and the new corporation

was on the verge of collapse when the All America Flying

Derby was organized and sponsored by American Cirrus

Engines, Inc. This was to be the longest air race held in

the world at the time-a 5,541-mile course that took the

contestants from Detroit to Texas, west to California, and

back to Detroit. All the entries were powered by one of the

engines manufactured by the sponsor, either the Cirrus or

Ensign engine. Eighteen entries competed in this event and

the Granvilles were among them. The engineering team,

spearheaded by Bob Hall, had produced the Model X, a trim

little low-wing monoplane finished in black and white,

powered by an American Cirrus engine supercharged by a Roots

blower (positive displacement) to develop 110 hp at 2100

rpm. The Model X was flown by Lowell Bayles, a quiet, slim

bachelor who was flying as copilot on the Fords the Tait's

owned and operated between Boston, Springfield and Albany

Bayles was

born in Mason, Illinois. He had studied to be a mining

engineer but, after taking some flying lessons, was bitten

hard by "the flying bug". He bought a war surplus Jenny and

joined the legion of barnstormers who were attempting to eke

out an existence by "hopping" passengers from the pastures

of America. In Leesburg, Florida, Bayles had met Roscoe

Brinton and, together, they had returned to

Springfield where both became involved in aviation

activities, later teaming to form Brinton-Bayles Flying

Service.

On July 21,

1930, the All America Derby began in Detroit. Ten of the

entries completed the course and Bayles finished second,

averaging 116.4 mph. The Gee Bee had demonstrated its

dependability, although at one point Bayles had landed in a

farmer's pasture and procured a piece of bailing wire to

make some quick engine repairs. Lee Gehlbach won this event

and later played a prominent role in the Gee Bee story,

flying the larger and more famous racers.

Bayles later

bought the Gee Bee X, NR49V, and used it for his personal

transportation. Unfortunately, it was lost when

Roscoe Brinton was forced to bail out of it during an

air show in New Hampshire. Always the showman, upon being

trucked back to the field, Brinton mounted the platform and

told the crowd, "You wouldn't get a show like that in the

National air races for what you paid here."

A total of

nine of these Sportsters were built with a number of

different powerplants. Eventually those with in-line engines

were referred to as Model D's, while those with radial

engines were called Model E's. The official CAA report on

the Menasco powered Sportster gave it the highest ratings in

every respect. During certification tests it took off in

nine seconds after a run of only 360 feet. Its rate of climb

was 1,100 feet per minute. Prices ranged from approximately

$4,800 to $5,500 depending on the powerplant selected.

Later in

1930, a larger version of this Sportster evolved, known as

the Senior Sportster and designated as the Model Y. Only two

of these were built and a number of power options were

available. The Model Y was a two-place ship that could be

converted to a "oneholer" by removing the front windshield

and placing a metal fairing over the front cockpit. Licensed

as NR11049 (or X11049), and NR718Y, they had a span of 30

feet and a length of 21 feet. Both were eventually lost in

crashes.

The

depression continued to plague the nation and Granville

brothers was not exempt from the difficult times. It was a

constant battle to keep their heads above water. In

mid-1931, Bob Hall, the chief engineer of the fledgling

corporation, mentioned the money to be made in racing

contests such as the Thompson race. Hall was convinced that

he could design a plane that could capture such a rich prize

and work was begun on this project in the middle of July.

Meanwhile, financial backing continued to be a problem. Hall

pounded the streets by day seeking backers and toiled by

night on the design and construction of the new racer.

Finally, with sufficient funds, they formed the Springfield

Air Racing Association with James Tait as president. One of

their chief backers was Lowell Bayles, who had invested $500

for the privilege of flying the Model Z, as the racer would

be designated. Actually the Granvilles had very little money

invested in this ship. In these difficult times practically

everything was furnished by the manufacturers. Tubing, dope,

fabric, wheels, tires, and instruments were donated for

advertising purposes.

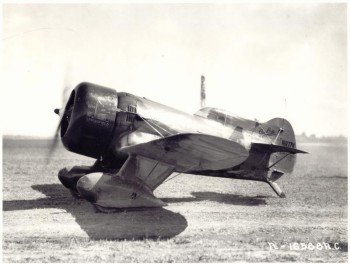

On August

22, 1931, Bob Hall's 26th birthday, the black and yellow

Model Z was rolled out of its hangar. Shorter and stubbier

than earlier models, it was already taking on the classic

Gee Bee appearance. Only 15 feet 1 inch in length, it was

powered by a Pratt & Whitney Wasp Jr., supercharged to 535

hp at 2400 rpm. The engine was loaned to the Granville

brothers by Pratt & Whitney. Bob Hall demonstrated his

confidence in his design by flying the first test flights

despite his limited experience. Christened "City of

Springfield'', the Model Z was flown by Bob Hall to the

National air races at Cleveland where they would learn the

results of their labours.

On September

1, Lowell Bayles, flying without shoes to improve his feel

of the rudder. raced over the Shell qualifying course at an

average speed of 267.342 mph. On one run he attained an

unofficial world record speed of 286 mph while 100,000

spectators gasped in wide-eyed

wonder. The next day Bayles won the 50 mile Goodyear trophy

race at a relaxed speed of 205.001 mph. Bob Hall, in Model

Y, NR11049, had a close brush with death when he hit a water

tank and clipped a few feet off a wing tip while turning on

a pylon too close to the ground. This didn't phase him as he

switched to the Model Z on September 5 to win the General

Tire and Rubber trophy as Bayles rested for the upcoming

Thompson trophy contest.

On September

6, Hall and the Model Z gained another first place for the

Gee Bee team in a free-for-all race. Maude Tait, daughter of

James Tait, captured the Cleveland Pneumatic Aero Trophy for

Women in the Model Y at the speed of 187.57 mph, a closed

course record for women. All of this led up to Bayles'

triumph in the stellar attraction of the meet, the Thompson

trophy race. The Gee Bees had cleaned up at Cleveland and

shares in their venture that had originally sold for $100

were now worth five times that. The Granvilles returned to a

victory parade and banquet in Springfield with cash in their

pockets and a determination to go after the world's speed

record and to ready themselves for the 1932 campaign.

First, the

"City of Springfield" was fitted with a new 750 hp Wasp Sr.

R-1340 engine. Arrangements had been made with the

authorities at Detroit's Wayne County airport to set up the

speed course and Maude Tait would also make an attempt at

the women's record in the Model Y while at Detroit. On

November 6, Bayles took off from Springfield to fly to

Buffalo where an 8 foot 2 inch fixed pitch propeller was

installed at the Curtiss Reed plant. After the arrival at

Detroit, Bayles rnade three attempts at the speed record

that were aborted as engine troubles plagued the "City of

Springfield". On one trial run he had attained a speed of

314 mph and prospects of a record performance appeared good.

Only the average of four runs could be given record

consideration, so the speed mark continued to elude them.

Maude Tait was equally unsuccessful and returned to

Springfield for her marriage to Attorney James P.Moriarty.

On November

30, Bayles was ready for another assault on the record. This

time it was the failure of the timing cameras that stymied

Bayles despite the fact that he attained a speed of 284.5

mph on one of his runs.

On the

afternoon of December 1, 1931, Bayles again went after the

elusive speed record, making four runs over the F.A.I. 1.8

mile (3 km) course. The existing world's record was 278.4

mph and it was necessary to surpass this by 4.97 mph to

claim a record. For a while it appeared that he had achieved

284.7 mph, but a recheck on December 2 showed an average of

281.75, so once more the record slipped from their grasp.

On December

5, the 31 year old Bayles was ready again. Shortly after 1

p.m. he took off and climbed to 1,000 feet to start his dive

for the run which had to be made below 162 feet. Roaring

into the three-kilometer course at approximately 150 feet

above the ground, the Gee Bee was travelling at tremendous

speed when the plane suddenly pitched up sharply and the

outer half of the right wing folded back. The aircraft did

two and a half fantastically fast snap rolls and crashed in

a ball of flames. The wreckage was scattered over 600 feet

and the shy, slim Bayles was killed instantly. Ironically

Bayles was to have been married on December 13 to Miss

Gertrude St. Marie of Newton, Illinois. His death was a

terrible shock to all involved since he was like one of the

brothers and had exhibited great faith in the aircraft.

A motion

picture of the crash was examined frame by frame and the

final conclusion was that a loose gas cap had caused all the

trouble. Apparently it had vibrated loos,

crashed through the windshield and incapacitated

Bayles, at least breaking his goggles and possibly rendering

him unconscious. It was here that the sudden change of

attitude occurred. According to designer Hall, the plane was

sensitive longitudinally and the sudden change of pitch

caused the wing to fail. Pieces of the canopy, part of

Bayles' goggles and the gas cap found along the flight path

seemed to support these findings.

It must be

re-emphasized that the Granvilles

were not amateur experimenters who simply threw together a

succession of aircraft with bigger and bigger engines.

Granny always knew enough to attract highly skilled workers

to their organization and on their staff were such competent

aeronautical engineers as Bob Hall and Howell Miller.

Although construction methods were of the highest order it

seemed that the Gee Bees were often plagued by human errors,

material defects or careless maintenance that brought these

high-performance aircraft to grief.

It was only

a slight consolation when an exception was made to the

regulations to posthumously award the U.S. national land

plane speed record of 281.75 mph to Lowell Bayles on January

14, 1932, for his flights of December 1, 1931. Although an

air of gloom descended on the organization at their first

loss, plans went ahead for the 1932 campaign.

Engineer Bob

Hall had left the Granville camp at the end of November

1931. Russell Boardman, famed long-distance flyer, bought a

controlling interest in the Springfield Air Racing

Association and planned to pilot one of the two planes that

the Granvilles were planning for the 1932 races which would

be held at Cleveland from August 27 to September 5. For

these races the Granvilles, along with their new chief

engineer Howell W. Miller, built two planes, the R-1, begun

in May of 1932, wore racing Number 11, and the R-2 wore

Number 7. Number 11 was powered by an 800-hp Wasp Sr. T3D1,

while Number 7, designed for longer races such as the Bendix

transcontinental, had a larger gas tank and a 550-hp Wasp Jr.

Both had controllable pitch propellers, among the first used

in racing. Russell Boardman was chosen to fly Number 11, and

eventually Lee Gehlbach would pilot Number 7.

Boardman was

born near Middletown, Connecticut, on January 22. 1898, and

had purchased his first plane in 1921. For a while he took

over the Hyannis, Massachusetts, airport and had operated a

seaplane line from Boston to Hyannis. On July 28, 1931,

along with John Polando of Lynn, Massachusetts, he had flown

a Bellanca from Floyd Bennett field in New York to Istanbul,

Turkey, to establish a distance record of 5,011 miles. At

the Omaha air races in May of 1932, he won a free-for-all

race in the Gee Bee Model Y that Maude Tait had raced in

1931. The following day he demonstrated his versatility by

winning the Charles Holman acrobatic trophy.

Demonstrating the scientific nature of their research, the

Granvilles constructed a wind tunnel model of their barrel-fuselaged

racer and had it subjected to tests in the New York

University wind tunnel. A year later, on May 18, 1933,

Granny and his chief engineer, Howell W. Miller, presented a

paper to the Society of Automotive Engineers in New York

City describing the design and construction of their

now-famous racers. Obviously they felt that they had two

sound, viable contenders for the prizes offered in the

upcoming races.

On August

10, painter George Agnoli finished the fancy scalloped red

and white paint job on the R-1. On the 12th it was rolled

out of its hangar to sit gleaming in the sunshine. Final

adjustments postponed the first flight until the following

day. On August 13, shortly after nine o'clock, Russ Boardman

took off his coat, slipped on a parachute and flew the R-1

to the Bowles Agawam field across the Connecticut river. The

performance figures were exhilarating. The R-1 had hit 240

mph without half trying and Boardman felt confident that 300

mph was well within reach.

Robert and

Granny Granville were at Bowles when Boardman landed from

the first test flight. As they opened the door of the plane,

Boardman looked up at them, grinned and said, "You boys sure

build airplanes." His only complaint was that the ship

fishtailed during landing approach and apparently did not

have enough fin area. Work was immediately begun to rectify

that problem by adding two square feet of fin area and an

increase in rudder area to match the added fin.

On Tuesday,

August 16, Boardman was severely injured as he spun a Model

E Sportster into the trees on the Carew street side of the

Springfield airport as he was flying to Agawam to complete

the tests on the revamped R-1. With two weeks remaining

before the start of the races, neither aircraft had a pilot.

Applications flooded the Granvilles from every pilot in the

country who had any ambitions of appearing in the Cleveland

races. Finally, on August 22, Lee Gehlbach was chosen to fly

the R-2. He would ferry the R-2 to Burbank to fly the Bendix

race from there to Cleveland. Oil temperature problems were

already starting to show up which would plague the R-2 over

the next few weeks.

A stroke of

fate interjected a new name into the Gee Bee saga. At

Wichita, Kansas, Jimmy Doolittle was test flying his Laird

"Super Solution", which had been extensively modified for

the 1932 races. When he found that he couldn't get the

wheels down, he was forced to belly his aircraft in,

eliminating it from further competition, but emerging

unhurt. On August 27, when it was apparent that Russ

Boardman would be unable to compete in the National air

races, Granny made telephone arrangements with Doolittle for

him to fly the R-1. On August 28, Doolittle arrived at

Springfield. While everyone expected him to take a turn or

two around the field to familiarize himself with the new

aircraft, dubbed by the press as "The Flying Silo", he

simply climbed in, headed west and never altered his course.

Less than two hours later the Granvilles received a telegram

stating simply, "Landed in Cleveland O.K., Jim."

Lee Gehlbach

indicated his confidence in Number 7 when he told members of

the press, "Number 7 is the most wonderful handling ship

I've ever flown. Doolittle added his praise of Number 11 by

stating. She s got plenty of stuff. I gave her the gun for

just a few seconds and she hit 260 like a bullet without any

change for momentum and without diving for speed and she had

plenty of reserve miles in her when I shut her down.

Only four planes were entered in the Bendix race from

Burbank to Cleveland and Gehlbach had to be considered as

one of the pre-race favourites, but engine troubles plagued

him all across the country. Robert Granville recalls that

"The Gee Bee was throwing oil so badly that Gehlbach landed

in Illinois and removed the oil splattered canopy so that he

could see." He finished a disappointing fourth, an hour and

twenty minutes behind the winner, Jimmy Haizlip, who was

flying the Wedell-Williams Special No. 92.

Doolittle fared better in the Thompson trophy race. On

September 5, nursing a hay fever attack, he blazed around

the pylons at a winning speed of 252.686 mph. Among those

who witnessed his victory were his tu-o sons, ten year old

John and James Jr. Lee Gehlbach finished fifth, and Bob

Hall, the former Granville engineer, was sixth in the field

of eight in his Springfield "Bulldog" racer.

While at Cleveland, Doolittle set a world's land plane speed

mark over the regulation F.A.I. three

kilometre course that had been set up for a series of

speed dashes sponsored by the Shell Oil Co. On August 31,

the 35year-old Doolittle averaged 293.193 mph on four runs

over the speed course but this did not qualify as an

official record since he didn't have a barograph in the

plane to confirm that he was below the required 162 feet (50

meters) during his runs. He subsequently made four more runs

on September 1, averaging 282.672 mph, just .77 mph short of

that required to claim a new record. On his final run it

appeared to the horrified spectators that he was about to

brush some trees just north of the field. Later Jimmy said,

"I was nowhere near them. I must have been at least four

feet over them."

At the Eastern States Exposition in September of 1932,

Jimmy, in speaking of Z. D. Granville. said, "He builds a

most excellent airplane and it was the airplane that did the

job." Finally, in a letter dated September 7, 1932, and

addressed to Granville Brothers Aircraft. Doolittle

commented, "Just a note to tell you that the big Gee Bee

functioned perfectly in both the Thompson trophy race and

the Shell speed dashes. With sincere wishes for your

continued success, I am, as ever,

Jim.

Preparations were immediately started for the 1933 races.

Number 11 was fitted with a P& W Hornet and a rudder with

increased area. Number 7 had the Wasp Jr. replaced with a

new Wasp Sr. and the old engine cowl from the R-1. A new

wing with greater span and chord was installed as well as a

larger rudder, identical to the new R-1 rudder. AISO7 in

1933, work was begun on the design of a two place, long

range racer to be built for Jacqueline Cochran and designed

to compete for the $48,O00 purse offered in a

London-to-Melbourne race scheduled for 1934. This plane was

called the Q.E.D., from the Latin phrase, "quod erat

demonstradum", meaning that the solution of a given problem

has been demonstrated. However, it would be tragically

demonstrated that all the problems associated with high

speed flight had indeed not been solved.

The 1933 National air races were to be held in Los Angeles

from July 1 through July 4, with the finish of the

transcontinental Bendix race from New York as one of the

highlights. After being received at City Hall on June 6 by

Mayor O'Brien of New York, Boardman, now recovered from his

earlier injuries, and 22-year-old Russell Thaw, in the

re-engined R-1, and the modified R-2, left Floyd Bennett

field on the morning of July 1, 1933 along with Roscoe

Turner, Lee Gehlbach, Jim Wedeli and Amelia Earhart. Thaw

took off at 5:52 a.m. and Boardman followed, being the last

to depart. Thaw used almost the entire length of the field,

dragging his tail wheel as he struggled to get his heavily

laden plane into the air. Boardman, with a lighter load and

higher horsepower, made a perfect take-off and streaked

westward.

Boardman and Turner had announced that they would refuel in

Indianapolis while the others would let their fuel

consumption govern their landing places. Preliminary plans

called for Thaw to land at St. Louis and Amarillo, but his

high rate of fuel consumption caused him to land at

Indianapolis. Turner arrived at Indianapolis at 6:06 a.m.

and within ten minutes he was once more winging his way

westward. Thaw was the next to land. Contrary to many

published reports, he made a perfect landing. On all earlier

Gee Bees the Granvilles had manufactured their own shock

struts. Now their racers were equipped with a commercially

manufactured strut. In making a rapid 180-degree turn to get

back to the refuelling area, one of these struts collapsed

and the left wing tip was damaged near the outer aileron

hinge as it struck the runway.

Since it looked as if the damage could be readily repaired,

the plane was wheeled into a hangar and work was begun to

restore it to flying condition. Boardman was the next to

arrive and he chatted with Thaw as his plane was refuelled.

Then he took off with 200 gallons of fuel on board. At about

40 feet in the air, he lost control of Number 11, and it

flipped on its back and crashed, fatally injuring Boardman,

who died on the morning of the 3rd, leaving a wife and

four-year-old daughter, Jane. Thaw was so shaken that he

withdrew from the race at that point.

The other entries were also plagued with misfortune. Lee

Gehlbach, flying a Wedell-Williams racer, was forced to land

near New Bethel, Indiana, with a clogged fuel line, crashing

through a fence but emerging unhurt, and Amelia Earhart, in

a Lockheed Vega, was forced down in Kansas. Roscoe Turner

won the race in 11 hours and 30 minutes, picking up the

$5,050 first prize plus $1,000 for setting a new East to

West record. Wedell, who finished second, won $2,250.

It was a horrible blow for the Granville brothers. In a few

minutes they had lost both planes and one pilot. Robert

Granville recalls, "I guess it was the point where our luck

started to go bad."

Boardman's brother, Earle, also a pilot, was with him when

he died. On July 4, he flew Russ' body east to Hartford,

Connecticut, stopping to refuel at Syracuse, New York. On

July 6, 1933, Russell Boardman was laid to rest in the Miner

cemetery in Middletown, Connecticut, while six planes

circled overhead and dropped flowers. Among those present

was John Polando of Lynn Massachusetts, with whom Boardman

had made his long distance flight to Turkey.

Granny repaired Number 7, but within a few days Jim Haizlip

cart-wheeled it across the Bowles

Agawam field. Although he was uninjured, the plane was a

total loss. One more tragedy took place in 1933 that

reflected unfairly on the reputation of the Granvilles. On

September 4, 1933, the newest Model Y, NR718Y, originally

built for the E. L. Cord Corporation, but now owned by

Arthur Knapp of Jackson, Michigan, and being flown by

26-year-old Florence Klingensmith of Minneapolis in the

International air races at Chicago, crashed and was

destroyed. Originally powered by a 215-hp Lycoming R-680

engine, it now sported a 450-hp Wright J6-9 Whirlwind.

Miss Klingensmith was running with the leaders in the

seventh lap of the Phillips trophy free-for-all race when

the fabric on the right wing split between the first and

second ribs. Although Granny later insisted that this should

not have affected the integrity of the aircraft, she leveled

off and flew to the southeast for three miles before hitting

a tree at the corner of Glenview and Shermer Roads in

Glenview, Illinois.

She had evidently tried to bail out at the last minute for

her chute was deployed beside her, but she had been killed

instantly. Later, the remaining Model Y, NR11049. formerly

flown by Maude Tait, was lost when a propeller blade broke,

the engine tore loose from its mountings, and it spun into

the Atlantic Ocean after a take-off from

North Beach (now LaGuardia) field. Both of these planes had

passed from the influence of the Granvilles and had been

modified by their new owners, but the reputation of the Gee

Bees suffered unfairly from their loss.

During the fall of 1933, Z. D. Granville, Howell Sliller,

and Donald Delackner opened a consulting engineering office

in New York City in the hopes of continuing development of

certain commercial projects such as four, six and eight

place airplanes. As far as racers went, they were left with

the shattered remains of the R-1 and R-2. From the remains

of the R-1 and the R-2 the Granvilles built another racer,

christening the resultant plane "Intestinal Fortitude". It

was known as "International Supersportster" Model R-3. The

plan was for Roy Minor to fly it in the Chicago races of

1933.

After "Intestinal Fortitude" was assembled. Grannv planned

to fly to San Antonio to deliver a Sportster that he still

owned to a customer in that Texas City. En route. he planned

to visit Florida and the Mardi Gras in New Orleans.

Approaching a landing at Spartenburg. South Carolina, on

February 12, Granny suddenly noticed that there was

construction in progress and his only safe landing area was

blocked by two workers unav. are of his approach. As he

pulled up, his engine coughed and died and he spun in from

75 feet. The 35-year-old Granny died en route to the

hospital leaving a wife and two children.

Shortly after Zantford's death, the Gee Bee organization was

sold at a sheriffs sale. However, financial backing was

found to continue work on the big Q.E.D. Wesley Smith and

Jacqueline Cochran flew this plane in the MacPherson

Robertson London-Melbourne race and made it as far as

Bucharest, Romania. Here the aircraft was damaged in landing

when the flap system failed to operate properly. Earlier in

1934, Lee Gehlbach had flown the Q.E.D. in the 1934 Bendix

race. Plagued by cowl troubles, he arrived in Cleveland too

late to even place in the race. As if there were not enough

trouble, Roy Minor had stood the R-3, also known as the

R-1/R-2, up on her nose in a drainage ditch in Springfield

during some tests and that eliminated that aircraft from any

of the 1934 events.

With all its power, the R-3 had a tendency to float during

landing, causing Minor to overshoot on landing and touch

down at mid-field. Earlier a thunderstorm had drenched the

field and he found he could not stop on the wet grass. The

plane went up on its nose in the ditch, made one or two

revolutions on its prop and then leaped over the fence to

land upright on its gear in the adjoining street. Needless

to say, Minor was thoroughly disgusted as he climbed out of

the aircraft and tossed his helmet and goggles over the

fence to the Granvilles, who had raced to see what remained

of the aircraft. The resulting damage eliminated the ship

from all competition during that year.

The Granvilles hoped to attract some military business by

demonstrating the Q.E.D. throughout Europe. Although some

demonstrations were arranged, no orders were forthcoming.

Returning the ship to the United States, it suffered a

landing accident while on a demonstration flight for some

Chilean officials. Although no one was hurt, no orders

resulted from that event. Indeed, with a little luck at this

time and with the impending war, the Granvilles might have

taken their place among the prominent aircraft manufacturers

of the present era. But, unfortunately, whatever luck the

Granvilles had was almost invariably bad.

The 1935 Bendix race saw two Granville entries. The Q.E.D.

was flown by Royal Leonard and the composite R-3, renamed

the "Spirit of Right", was to be flown by 33 year old Cecil

Allen. Among Allen's backers were the Aero Educational

Research Organization of Pasadena and the Religious Patrons

Association. The R-3 had been modified by Allen. although

the Granvilles could no longer directly exert any control

upon its fate. Howell Miller had contacted Allen and offered

to aid in its reconstruction. When he was ignored. he did

stress to the new owner that in no case should the centre of

gravity be moved aft of 22 percent of the mean aerodynamic

chord.

The 1935 Bendix race was from the Union Air Terminal in

Burbank, California. to Cleveland. On August 30, Allen was

the last to take off. following Benny Howard, the eventual

winner, and Roscoe Turner, who was to finish second by only

23 seconds The "Spirit of Right" was decorated with the

cartoon character "Filaloola" bird that had adorned the

earlier successful Model Y, and the motto, "Over the Fence

and Out", and that's a succinct summation of its

performance.

Allen's plane, 22.5 feet in length with a 30 foot span, had

not performed well in tests and careened crazily at the

start of the Bendix. Staggering into the sky, Allen was only

two miles from the field when he lost control and crashed in

an open field. Allen had cut the ignition switch so there

was no fire, but the two witnesses who raced to the scene

found him dead in the cockpit. Allen had added some fuel

tanks and had test flown the aircraft with only the forward

tank filled. With the aft tank filled for this race, it was

later computed that the center of gravity was approximately

35-37 percent of the M.A.C. Again the Granville name was

defiled when, in fact, it should have been reported that

"they told him so". The Q.E.D. fared only slightly better,

making it as far as Wichita when engine trouble arose to

prevent the fans at Cleveland from getting a glimpse of the

Gee Bees in 1935.

The Granvilles were now just about finished in the field of

racing although Mark Granville and most of the workers at

the Granville plant built a new racer for Frank Hawks.

Sponsored by the Gruen Watch Company, it was called "Time

Flies" and was one of the most streamlined aircraft of all

time. A unique feature on "Time Flies" was that the pilot's

seat could be lowered about 12 inches in flight, allowing

the windshield to be retracted

flush with the fuselage.

The Q.E.D. was left alone to carry the memory of the

Granvilles to the leading air racing events that they had

once dominated. Lee Miles flew the Q.E.D. in the 1936

Thompson trophy race, averaging over 200 miles per hour for

the first 10 laps. Then engine trouble forced him to retire.

The jinx of the Q.E.D. continued.

By 1938, the Q.E.D. was in the possession of Charlie Babb, a

well known aircraft broker. After a complete overhaul of the

plane, George Armistead, one of Babb's pilots, was named to

fly it in the 1938 Bendix trophy race. Heading east

from Burbank, Armistead was over

Kingman, Arizona, when he noticed his oil pressure dropping

rapidly and the oil temperature climbing at an alarming

rate. Landing at Winslow, Arizona, he decided that there was

no use in attempting to resume the race.

Charlie Babb then sold the Q.E.D. to Francisco Serabia, the

president of TASCA, a Mexican airline. The plane was renamed

"Conquistador del Cielo and registered as XB-AKM. Serabia

called it the best plane I've ever flown". On May 24, 1939,

he flew the plane from Mexico City to New York, covering

2350 miles in just 10 hours and 47 minutes. On June 7,

Serabia vas ready to leave Bolling field in Washington.

D.C.. for the return flight to Mexico. As the plane roared

out over the Potomac river, the engine missed and faltered

and the plane plunged into the river. Serabia was trapped in

the cockpit and drowned in 15 feet of water. Later it was

determined that the cause of the accident was that a rag had

been left inside the cowl and had

been sucked into the carburettor air intake.

Later, the Q.E.D. was salvaged ``ith minimal damage. For a

time it sat at a Mexican Air Force Base at St. Lucia. (In

the 1960's. Alberto Sarabia, a cousin of Francisco Sarabia,

had the Conquistador del Cielo" restored to like new flying

condition. A round, domed museum to house the restored

aircraft was built in Ciudad Lerdo, Durango, Mexico and the

aircraft is presently enshrined in the middle of the room,

surrounded by floodlights that illuminate the aircraft night

and day. The museum is open to the public.) The surviving

Gee Bee Model A, N9OlK, is in the collection of the

Connecticut Aeronautical Historical Association at Bradley

Field in Windsor Locks.

What has become of the principals of this story? Edward

Granville worked for Pratt & Whitney in Connecticut for 40

years and retired in 1976 as Chief of Experimental

Construction. In 1977 Ed died at his home in Silver Lake,

N.H. Robert Granville was a foreman for Vought during World

War II, supervising the construction of Corsairs and

Kingfishers. In 1946 he moved to Maine where he purchased a

large farm near Skowhegan. Having sold most of the farm, he

and his wife, Eva, were living in North Cornwall, Maine,

when he passed away on 13 Nov. 1978.

Mark Granville was superintendent of the wind tunnel at

Pratt & Whitney when he died of a heart attack in Somers,

Connecticut, in the early 50's. Thomas Granville, who was a

welding foreman at Kaman Helicopters, died in May of 1974 of

heart trouble. Howell (Pete) Miller, the designer of the R-1

and R-2, is retired from Pratt & Whitney and lives in

Manchester, Connecticut. Robert Hall retired from Grumman

Aerospace Corporation as Vice President and now resides in

Hilton Head, South Carolina. Maude Tait Moriarty still lives

in Springfield, Massachusetts. Russell Thaw is reported to

be a postmaster in a small Connecticut town. While Granny's

wife, Alta, died in December of 1974, his son, Robert, works

for Pratt & Whitney in Hartford while his daughter, Norma,

is a medical doctor and blood specialist at a hospital in

Hartford, Connecticut.

The old Springfield field is no longer there, having been

turned into a shopping centre, but the birth of the

Granville aircraft at this site has not been forgotten. A

large mural in a restaurant depicts the landing of a Gee Bee

at the old airport and bears portraits of the five brothers.

One wonders how many busy shoppers in a nearby department

store pause to read a plaque erected in honour of the Gee

Bees and the Granville brothers. Indeed, the Gee Bee racers

will live forever in the memories of those who witnessed the

flights of these remarkable aircraft.

Gross

Weight 2280 lb Empty Weight 1400 lb Useful Load 880 lb Seats

1

Length

(overall) 15 ft 1 in Cowl Diameter 46 in Span 23 ft 6 in

Root Chord 50.4 in Rib Spacing 5.5 in Spar Spacing 25.5 in

Airfoil M-6 Incidence Angle 3 deg Dihedral Angle 4.5 deg

Wing

Area 75 sq ft Aileron Area 9.5 sq ft Stabilizer Area 8.4 sq

ft Elevator Area 6.9 sq ft Fin Area 2.2 sq ft Rudder Area

4.9 sq ft

Landing

Gear Travel 6 in Tires 23 inch Goodrich 6.5 x 10 Wheel Tread

71.75 in Wheel Fairing Width 10.5 in

High

Speed 270 mph Cruise Speed 230 mph Landing Speed 80 mph

Runway

Requirement 5000 ft @ SL

Range

900 sm

Powerplant P & W Wasp Jr (Supercharged) 535 hp @ 2400 rpm

Fuel 103 gal Oil 11 gal

Production 1 First Flight 8-22-1931

Construction

- Chrome

Moly steel tube fuselage. - Covered with fabric

Flight Controls Rudder - Cable Actuated Ailerons -

Torque tube actuated Elevator - Push pull tube and double

cables

Notes: - Winner of 1931 Thompson Trophy at 236.24 mph -

Qualification speed for 1931 Thompson (level flight, 1 pass

each way, averaged) 267.342 mph - Larger 750 hp Wasp Sr, new

prop and cowl were installed after the Thompson. - Destroyed

on a speed course, December 1931, Detroit, MI Zantford

Granville attributed the accident to a fuel cap coming

loose, passing through the windscreen and striking the

pilot. |