|

the

great air races of the 'Golden Age'

Bendix Trophy

In the United States, racing began with the Los Angeles

meet of January 1910, in which Glenn

Curtiss and Louis Paulhan

were the big winners. Paulhan was again victorious in the

grueling London-to-Manchester race

in which he beat a heroic effort

by the British aviator Claude

Grahame-White. It seemed, in fact, that Grahame-White

made more capital out of losing than

Paulhan did winning. Although he was a relative

newcomer, Grahame- White won the

Gordon- Bennett trophy at Belmont

Park, Long Island, in October

1910, making him an international

celebrity.

After Reims, a series of races were held across

Europe—Paris to Rome; and circuits

in France-Belgium and in

England—pitting, for the most part, Andre

Beaumont against Roland

Garros. Here, too, Garros seemed

to make more out of losing each time than

Beaumont did winning.

Garros finally won the races held

in Monaco in August 1914, a year after the first

Schneider Cup event, and then went on to be first to

cross the Mediterranean.

Glenn Curtiss

continued designing and building planes

in the 1920s for racing and exploring.

The Oriole, among the most popular,

was a versatile

and inexpensive plane that could fly a good race

one day,

deliver mail the next, and fly the Arctic the day after...

The war curtailed racing in

Europe, and in the United States

the vigorous litigation by the Wrights against anyone

they thought was infringing on their patents put a

damper on racing and on flying in general. After

World War I, the sons of

newspaper tycoon Joseph Pulitzer

established the Pulitzer Trophy

races in 1920. The huge turnout at

Mitchell Field, New York, proved that interest

was still there. A crowded

field—thirty-seven planes staggered just two minutes apart,

which meant nearly all of them

were on the 116-mile (186.5km) course at the same

time during most of the

race—circled the course three

times, with the winner, Corliss C. Mosley, in a Verville-

Packard biplane.

The first man to congratulate Mosley was Billy

Mitchell, now a hero of the war

and at this point still

highly respected in military aviation circles. Mitchell sold

the armed services on the

value of the Pulitzer (and other

races) as a means of improving aircraft design

and flying technique.

During much of the twenties, the army and

navy participated extensively in

racing, and they often flew

Curtiss racing planes, which became a profitable

portion of Curtiss’

business. The next Pulitzer races

were held in 1921 in Omaha, and

the event was part of a larger

cavalcade of aviation races and

displays called the National Air Congress.

These meets developed into

annual events that eventually came

to be called the National Air Races.

Many design

innovations had their first testing at the Nationals,

and some of the better aircraft went on

to race in the Schneider or

in other races. The Curtiss R3C-2 racer

in which Jimmy Doolittle flew

to victory at the Schneider races

in 1925 had been flown (minus the

pontoons) at the 1924 Nationals by

Cyrus Bettis, who walked off with the

Pulitzer that year. Along

with the planes, many a flier’s

reputation was made at these

events and many pilots became household

names of the period. Bert Acosta, a Curtiss test

pilot, for winning the 1921

Pulitzer in record from a

starting line instead of racing against the times of

their competitors flying separately. The race

gave rise to the

sport-within-a-sport of “pylon

polishing” (seeing who could fly

closest to the pylon

on the turn without hitting

it), which the crowd found nearly as enthralling as

the race. Being a pylon

judge was definitely not a job for

the squeamish.

In 1929 Henderson also convinced

manufacturer Charles U. Thompson

to sponsor a new Trophy event a

fifty-mile (80.5km) race open to

all aircraft. The Thompson Trophy

became the premier air-racing event

of the 1930s, bringing a

whole new cast of intriguing dark

horses into the spotlight, all trying to beat the army

and navy planes. The 1929 Thompson race was won by

Douglas Davis, flying a Travel Air

“Mystery” plane. (The

mystery turned out to be that the plane had a Whirlwind

engine, thought to be too

bulky for racing.) The big news

coming out of the race was that for the first time a

civilian plane had beaten a

government plane in a race. To

make matters worse, the third-place finisher

was also a civilian: Roscoe

Turner flying a Lockheed Vega.

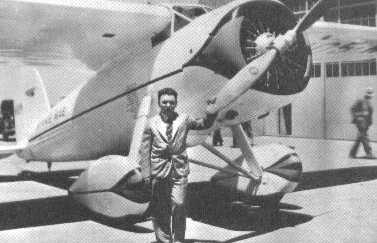

Wiley Post is seen here with Winnie Mae,

the Lockheed Vega aircraft

in which he made his legendary

round-the-world flights.

The 1930 Thompson Trophy

introduced the aviation world to

Benjamin 0. “Benny” Howard, an airmail flier

who built his own aircraft,

a racer marked DGA-3 (which Howard

said stood for “Damn Good Airplane”)

and which Howard called

Pete. Howard and Pete would become

fixtures at the Nationals throughout the

1930s, though Howard never

won a trophy. The year 1930 also

saw the debut of an unknown

barnstormer with a patch over one

eye, Wiley Post, who flew a Lockheed Vega

called Winnie Mae. The

field that year was rich in planes

and pilots that would ultimately become legendary in

aviation history:

The Thompson Trophy ward plaque.

This one was awarded to first-prize winner Cook Cleland in

1947.

Speed Holman flying Emil “Matty” Laird’s

Solution (which had not been

completed until hours

before the start of the race, and had been test-flown for

all of ten minutes), Frank

Hawks in one of two Travelair Air

“Mystery” planes built by Walter Beech, and several others.

The favourite plane that year was a Navy Curtiss Sea Hawk,

with a 700- horsepower Curtiss Conqueror engine. However the

navy plane crashed and Holman won the race. (In 1931, Holman

was killed in a crash while stunting in Omaha.)

The Gee Bee R2

in which Jimmy Doolittle won the Thompson

Trophy in 1932, with a record speed of 296 miles per hour

(474kph). Doolittle then quit racing, claiming the Gee Bee

was too

dangerous to fly. (Later analysis showed that the odd weight

distribution made it virtually impossible to control the

plane once

it went into any sort of roll.)

The 1931 Thompson competition saw the

unveiling of one of the most unusual aircraft ever to fly:

the Gee Bee. The name stood for the Granville Brothers, a

small airplane manufacturer in Springfield, Massachusetts.

The designer, Bob Hall, had no experience designing racing

planes, and the final design looked like a bad drafting

mistake—as if someone had forgotten to draw in the back half

of the aircraft. Amazingly, the Gee Bee flown by Lowell

Bayles beat Jimmy Doolittle flying a Laird Super- Solution

and took the Thompson home. Doolittle was impressed, and the

next year he flew a Gee Bee and won the Thompson. The

experience must have been a harrowing one, though, because

not only did Doolittle never again fly a Gee Bee, but he

also became a staunch opponent of air racing and testified

before Congress to have it banned.

In truth, the Gee Bee was configured as

it was because it housed an enormous Pratt & Whitney Wasp

engine. The plane was notoriously unstable and structurally

fickle; every Gee Bee ever built crashed sooner or later.

the Thompson

Trophy in 1932

Bayles, the 1931 Thompson winner, crashed

after the competition trying to set a land speed record in

the aircraft (which is how Doolittle got to fly the plane in

the first place). And in

1934, Zantford “Granny” Granville

died when a Gee Bee he was flying to a customer

crashed. That’s when Edward

Granville discontinued the line.

In 1931, a fourth major race, the Bendix

Trophy, joined the

Schneider, Pulitzer, and Thompson as the prestige races of

the period.

Plaster model of the Bendix Air Race Trophy.

The Bendix was no more

than the cross-country race to the

Nationals that was held informally

every year. The big winners of the

Bendix included Benny Howard, who

won it and the Thompson in 1935,

his banner year; Jimmy Doolittle; and Roscoe

Turner, ever the showman, winning it flying with

his pet lion cub.

Roscoe Turner accepting his third Thompson

Trophy in 1939.

Though he became a showman and a flamboyant businessman, the

Thompson victories attested to his great skill as an aviator

The Bendix was taken very seriously because it was a

race that related directly to the desire to

use aviation to traverse

the vast distances of the United States. It encouraged

cross-country speed flights by

non-contestants that extended the

capabilities of long-distance flight. Frank

Hawks and the Lindberghs established cross-country

records in the early 1930s, the latter

proving in their Lockheed

Sirius that airplanes could fly best high over

storms in the rarefied

atmosphere above fifteen thousand

feet (4,57kn). All these records were to fall, however,

when a brash young movie

producer named Howard Hughes,

flying an open-cockpit Northrop Gamma

mail plane (which he had personally enhanced by

installing a powerful Wasp engine),

established records on an

almost yearly basis in the early to mid-1930s, culminating

in his January 1937 flight from

Los Angeles to Newark in seven

hours, twenty-eight minutes, and

twenty-five seconds.

|